Presidential candidates Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders have proposed expensive across-the-board increases in Social Security benefits, premised on the idea, as Warren says, that “It’s too hard to save enough for a decent retirement — and it’s only getting harder.” Congressional Democrats are ready to back the candidates’ promises, with near-unanimous House Democrat support for legislation to expand Social Security. But data from the Congressional Budget Office tell a very different story: over the last four decades, retirees’ incomes have risen at over twice the rate of salaries for working-age Americans, thanks to higher retirement savings and increased work in retirement. The presidential candidates should reconsider whether boosting Social Security for middle and high-income retirees should be a top priority.

Retirement security is a hugely important issue, both to Americans trying to boost their savings and for policymakers thinking about Social Security and retirement savings programs.

But in many ways, we’re flying blind because we lack solid data. Most facts and figures about retirement incomes are based on household surveys, where the government asks retirees how much income they receive from Social Security, pensions, earnings and so on. From these survey responses come figures regarding the poverty rate among retirees, the share of income retirees receive from Social Security, or how much retirees draw from private retirement plans like IRAs and 401(k)s.

The simple problem is that many people answer those surveys incorrectly. For instance, Sen. Warren’s campaign cites data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Current Population Survey (CPS) finding that “About half of married seniors and 70% of unmarried seniors rely on Social Security for at least half of their income.” But Census Bureau research finds that these figures are exaggerated, because the CPS data dramatically understate retirees’ true incomes. In fact, IRS data show the median retiree household’s income is fully 30% above what is reported in the Current Population Survey. And the true poverty rate among retirees is about two percentage points lower than the 8% rate that’s commonly reported. Unfortunately, these IRS data aren’t available to most researchers.

That’s why data released by the Congressional Budget Office are so important. The CBO figures are based on IRS data which more accurately capture the different sources of income that retirees rely on. And since the CBO data range from 1979 through 2016, we can see how retirees’ incomes have changed over time.

And the news is surprisingly good.

To capture what people think of as retirement income, I add together Social Security benefits, earnings in retirement, investment and retirement plan income, and means-tested benefits that are paid in cash, such as Supplemental Security Income (SSA) and food stamps benefits.

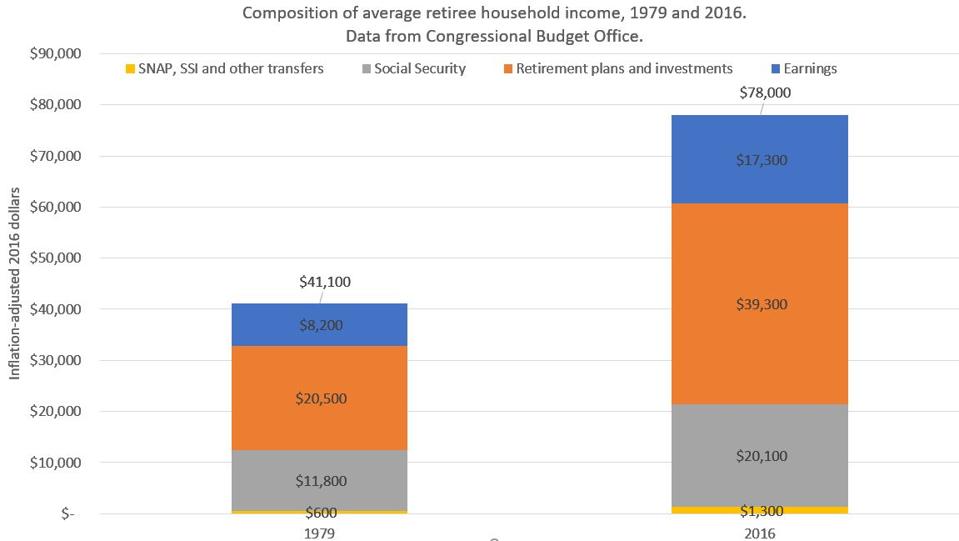

On average, household retiree incomes grew from $41,100 to $78,000 between 1979 to 2016, a 90% increase over and above inflation. Is that good or bad? Well, over that same period, average salaries for working-age households grew by only 39% above inflation, which shows that the relative economic status of retirees has increased considerably over the past four decades.

The CBO data confirm that retirees are upwardly mobile. Back in 1979, retirees were a disproportionately poor group, with a retiree household more than twice as likely to be in the poorest fifth of the overall population than in the richest fifth. Today, seniors are disproportionately rich: retirees in 2016 are 50% more likely to be in the top fifth of the income distribution than in the bottom. That’s a remarkable change in the economic status of the elderly.

What drove retirees’ incomes upward? Increased Social Security benefits helped, rising 70% from $11,800 per household in 1979 to $20,100 in 2016. But that’s not where the real action was. Retirees’ incomes from retirement plans and investments increased by 92%, from an average of $20,500 to $39,300, while earnings in retirement skyrocketed 111% from $8,200 to $17,300 per year.

cbo – retirement incomes 1979 and 2016

The presidential candidates may say that saving for retirement has gotten harder, but the data say different: both retirement savings and benefits from private retirement plans have never been higher. Candidates may say that Americans can’t stomach an increase in the Social Security retirement age, but Americans are claiming benefits later and working longer. And contrary to candidate claims, retirees today are actually less reliant on Social Security than in the past.

These figures should cause some of the presidential candidates to think twice about ambitious, but costly, proposals to expand Social Security benefits. Yes, strengthening the Social Security safety net for low-income retirees makes sense. And it’s not very expensive, either. I’ve argued for reforms that would virtually eliminate poverty in old age, while holding the line on tax increases.

But raising benefits across the board, including for middle and upper income retirees whose incomes have already risen rapidly, isn’t necessary. And those are expensive benefit hikes that require a nearly one-third increase in Social Security revenues. Social Security’s actuaries find that the most prominent House Democratic bill would raise Social Security payroll taxes by $833 billion in the first 10 years alone. That money might be better spent elsewhere or not spent at all.

A presidential campaign isn’t just about proposals, it’s about priorities. It’s about knowing what policy changes should be first in line when it’s difficult to pass new laws and even tougher to pay for them. And raising benefits for middle and high-income retirees whose incomes already outstrip those of working-age Americans shouldn’t be the highest priority.