This article is part of a series; click here to read part One.

Let’s continue to review the last 3 guidelines in the manifesto for my approach to retirement income planning.

Getty

Approach retirement income tools with an agnostic view

The financial services profession is generally divided between two camps: those focusing on investment solutions and those focusing on insurance solutions. Both sides have their adherents who see little use for the other side. But the most efficient retirement strategies require an integration of both investments and insurance. It is potentially harmful to dismiss subsets of retirement income tools without a thorough investigation of their purported role. In this regard, it is wrong to describe the stock market as a casino or to dismiss annuities or permanent life insurance as expensive and unnecessary.

Click here to download our resource, How Long Can Retirees Expect to Live Once They Hit 65?

For the two camps in the financial services profession, it is natural to accuse the opposite camp of having conflicts of interest that bias their advice, but each side must reflect on whether their own conflicts color their advice. On the insurance side, the natural conflict is that insurance agents receive commissions for selling insurance products and may only need to meet a requirement that their suggestions be suitable for their clients. On the investments side, those charging for a percentage of assets they manage naturally wish to make the investment portfolio as large as possible, which is not necessarily in the best interests of their clients who are seeking sustainable lifetime income and proper retirement risk management. Meanwhile, those charging hourly fees for planning advice naturally do not wish to make their recommendations so simple that they forego the need for an ongoing planning relationship. It is important to overcome these hurdles and to rely carefully on what the math and research show. This requires starting from a fundamentally agnostic position.

Start by assessing all retirement assets and liabilities

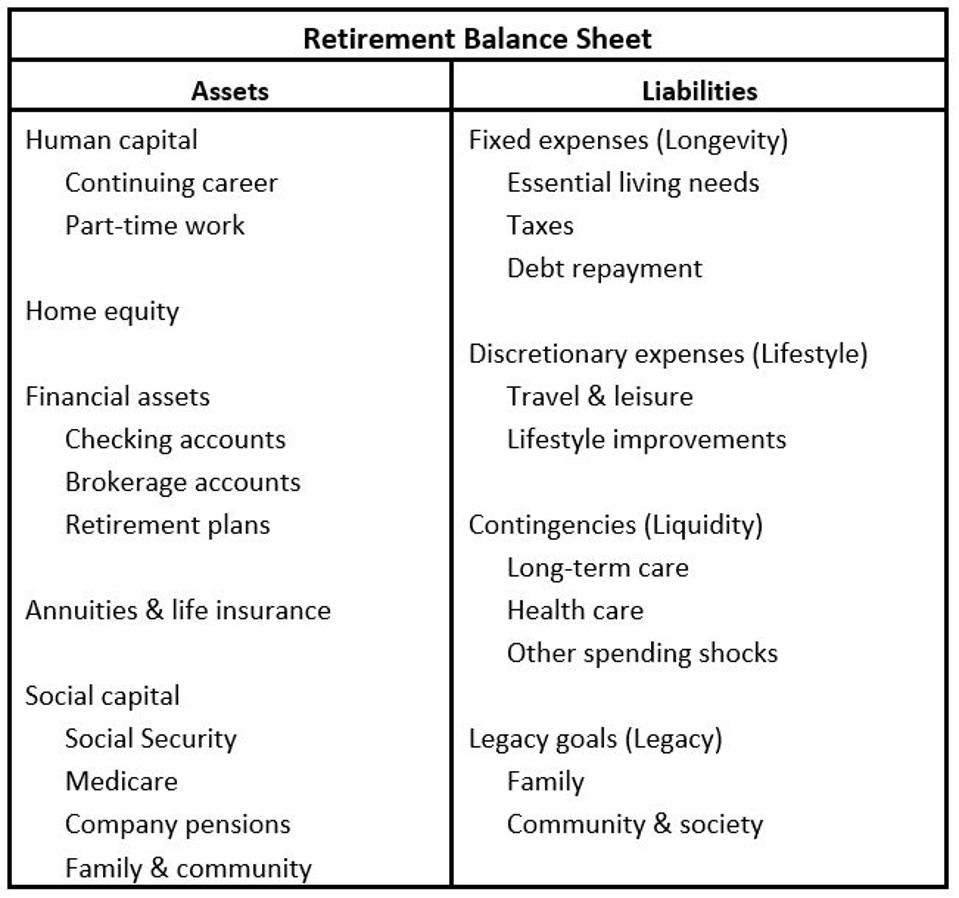

A retirement plan involves more than just financial assets. The retirement balance sheet is the starting point for building a retirement income strategy. At the core is a desire to treat the household retirement problem in the same way that pension funds treat their obligations. Assets should be matched to liabilities with comparable levels of risk. This matching can either be done on a balance sheet level, using the present values of asset and liability streams, or it can be accomplished on a period-by-period basis to match assets to ongoing spending needs. Structuring the retirement income problem in this way makes it easier to keep track of the different aspects of the plan and to make sure that each liability has a funding source. This also allows retirees to more easily determine whether they have sufficient assets to meet their retirement needs or if they may be underfunded with respect to their goals. This organizational framework also serves as a foundation for choosing an appropriate asset allocation and for seeing clearly how different retirement income tools fit into an overall plan.

Exhibit 1.1 provides a basic overview of potential assets and liabilities to consider.

Exhibit 1.1: Basic Retirement Assets and Liabilities

Retirement Researcher

Distinguish between technical liquidity and true liquidity

An important implication from the retirement balance sheet view is that the nature of liquidity in a retirement income plan must be carefully considered. In a sense, an investment portfolio is a liquid asset, but some of its liquidity may be only an illusion. Assets must be matched to liabilities. Some, or even all, of the investment portfolio may be earmarked to meet future lifestyle spending goals. Curtis Cloke describes this in his Thrive University program for financial advisors as allocation liquidity. Retirees are free to reallocate their assets in any way they wish, but the assets are not truly liquid because they must be preserved to meet the spending goal. Assets cannot be double counted, and while a retiree could decide to use these assets for another purpose, doing so would jeopardize the ability to meet future spending. In this sense, assets are not as liquid as they appear.

This is different from free-spending liquidity, in which assets could be spent in any desired way because they are not earmarked to meet existing liabilities. True liquidity emerges when there are excess assets remaining after specifically setting aside what is needed to meet the household liabilities. This distinction is important because there are cases when tying up a portion of assets in something illiquid, such as an income annuity, may allow for the household liabilities to be covered more cheaply than could be done when all assets are positioned to provide technical liquidity.

In very simple terms, an income annuity that pools longevity risk may allow lifetime spending to be met at a cost of twenty years of the spending objective, while self-funding for longevity may require setting aside enough from an investment portfolio to cover thirty to forty years of expenses. Because risk pooling and mortality credits allow for less to be set aside to cover the spending goal, there is now greater true liquidity and therefore more to cover other unexpected contingencies without jeopardizing core spending needs. Liquidity, as it is traditionally defined in securities markets, is of little value as a distinct goal in a long-term retirement income plan. It must be true liquidity to count.

This is an excerpt from Wade Pfau’s book, Safety-First Retirement Planning: An Integrated Approach for a Worry-Free Retirement. (The Retirement Researcher’s Guide Series), available now on Amazon.