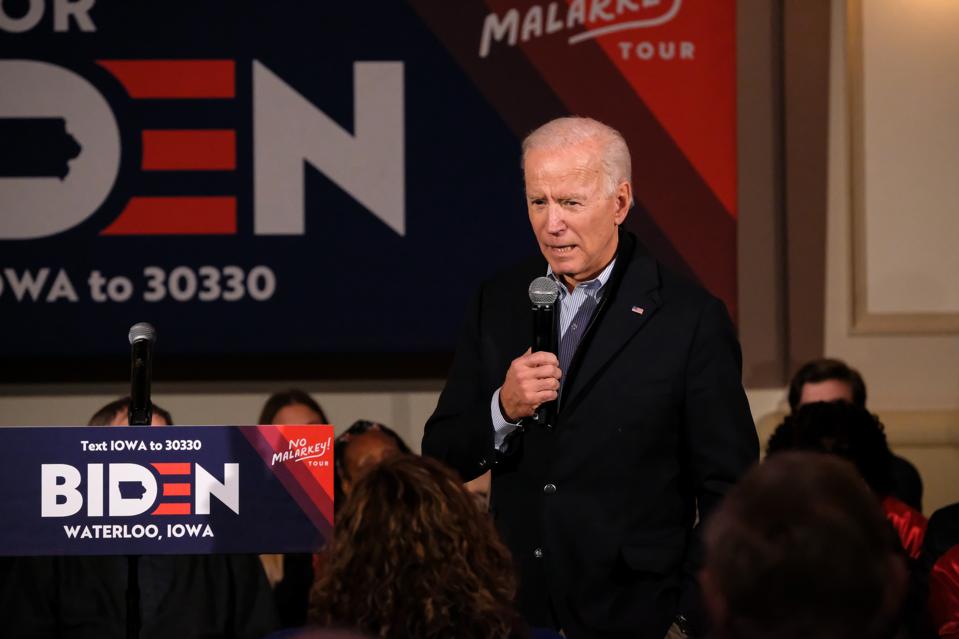

WATERLOO, IOWA, DECEMBER 5, 2019: Presidential candidate Joe Biden addresses supporters.-(Photo … [+]

When I heard that Democratic presidential hopeful Joe Biden was proposing to raise taxes by $3.2 trillion over 10 years, I flashed back to Walter Mondale and thought: My, how things have changed.

Mondale, like Biden, was a former vice-president and political moderate who was looking to gain the Oval Office. Mondale, in what was sadly—for him—the most memorable phrase of his 1984 campaign against Ronald Reagan—explicitly promised to raise taxes. In what has since been known as the Mondale moment, he said this: “Mr. Reagan will raise taxes, and so will I. He won’t tell you. I just did.”

Mondale insisted his tax hikes would target the wealthy and Reagan’s wouldn’t. It didn’t matter. In the election, Reagan got 525 electoral votes. Mondale got 13. He lost the popular vote by 18 million.

Soft-peddling tax hikes

That was, gulp, nearly 35 years ago. And in the eight campaigns since, no major Democratic presidential candidate was willing to so aggressively promote their tax increases.

Sure, most put forward a mix of relatively modest tax hikes on the wealthy and small tax cuts for everyone else. But on the stump they barely acknowledged these proposals, and never gave them the prominence Mondale did.

Not until this year. Among Democratic presidential candidates, raising taxes on the rich has become a thing. A big, loud, high-profile thing.

Which brings us back to Biden. He’s reportedly proposing a tax hike of $3.2 trillion over 10 years. Most, though not all, of those tax increases would be paid by high-income taxpayers and corporations. While the campaign has not yet released details, multiple published reports say it would, among other things, tax capital gains as ordinary income, raise the top individual income tax rate to its 2017 level of 39.6 percent, limit itemized deductions for high-income taxpayers, and raise the corporate income tax rate to 28 percent, backstopped with a 15 percent minimum tax and a 21 percent rate on foreign profits.

A massive tax increase

By recent standards, Biden would be proposing a massive tax increase. But, of the three Democratic hopefuls registering double-digit national support in the (still-early) polls, Biden has the most modest tax hike by far. His supporters say raising taxes by about 1.2 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is prudent. His critics on the left say it is not nearly enough.

By her own count, his rival Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) would raise taxes by more than $20 trillion over 10 years (7.5 percent of GDP). Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) has proposed his own long list of tax hikes on the wealthy— including a wealth tax, a financial transactions tax, and higher individual income tax and capital gains tax rates— to pay for his expansive spending agenda.

Suddenly, raising taxes—on the rich at least—has become a box Democrats feel the need to check. Given the lack of real public interest in controlling the burgeoning budget deficit, Democrats might have gotten away with ignoring the cost of their health care, education, housing, and environmental programs, and not highlighting their proposed tax hikes at all. After all, President Trump and the Republicans ignored the deficit with their $1.5 trillion tax cut in 2017.

Bragging on tax hikes

But, here’s the thing: Most Democrats running for president don’t seem to want to downplay their proposed tax hikes. Rather, they want to brag on raising taxes on the wealthy and corporations. Not just as a means to an end—fiscal prudence—but as an end in itself.

Public opinion surveys suggest this approach isn’t as bad an idea as it was in Mondale’s day. Most Americans feel the taxes they pay generally are fair, but believe the wealthy and corporations are not paying enough.

President Trump, of course, is unlikely to make fine distinctions about just whose taxes the Democrats would raise. Instead, he’ll likely propose new tax cuts of his own and blast his opponent for proposing the biggest tax increases in history (Not true in Biden’s case. True for Sanders and Warren, but only if you ignore the taxes the US raised to fight World War II).

Changing the dynamic

Mondale made his tax vow at the Democratic convention in July, 1984, when he already was well behind Reagan in public opinion polls. If it wasn’t quite an act of desperation, it was an aggressive effort to change the dynamic of the campaign. It did that, but not in a good way. Instead of the usual post-convention bump, Mondale’s support sagged.

Of course, the current race is not the same. In December, 1983—the same point in that election cycle as we are today—Reagan was polling at above 50 percent. Trump is mired in the low 40’s and facing impeachment. So far, at least, all of the leading Democrats beat him in the popular vote in a head-to-head race.

The question for Democrats will be whether the proposed tax hikes on the rich that play so well among the Democratic base will have legs in a general election. We’ll soon find out whether 2020 really is so different from 1984.