WASHINGTON, DC – APRIL 06: Spring flowers bloom in front of the U.S. Supreme Court. The Court … [+]

Getty Images

Last week, President Trump reaffirmed the Administration will urge the US Supreme Court to overturn the entire 2010 Affordable Care Act. While the High Court decision could eliminate insurance coverage for millions of Americans, tossing the ACA also would result in a major tax cut largely benefiting high-income households.

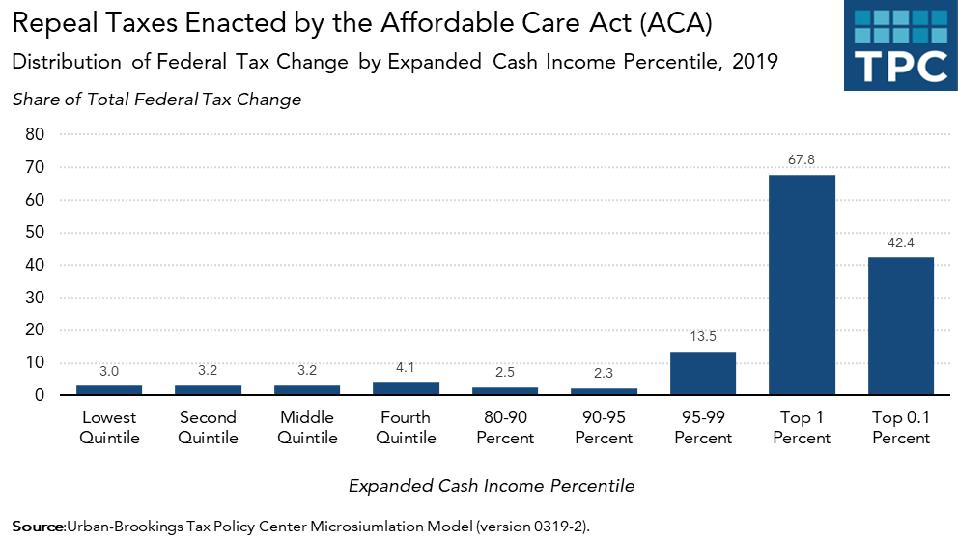

In 2019, overturning the ACA would have cut taxes by about $35 billion to $40 billion. The Tax Policy Center estimates that the highest income 1 percent of households (those making about $819,000 in 2019) would receive about two-thirds of the benefit of these tax reductions, while those in the top 0.1 percent (who make $3.8 million or more) would get about 42 percent. Households making $91,000 or less would receive less than 10 percent of the benefits.

Distributional effects of repealing Affordable Care Act taxes

Tax Policy Center

The Administration is backing the legal challenge—and the resulting tax cuts—at a time when some top aides are raising concerns about whether additional coronavirus relief would add too much to the federal budget deficit.

On average, repealing the ACA would cut taxes for the top 1 percent by about $32,000 in 2019 (or 1.9 percent of after-tax income) and by about $200,000 (or 2.5 percent of after-tax income) for the top 0.1 percent. Taxes for middle-income households would be cut by an average of $50, about 0.1 percent of their after-tax income.

The ACA included several tax hikes, some of which Congress repealed in the intervening years. But a handful remain, including the 3.8 percent Net Investment Income TAX (NIIT) and the 0.9 percent additional Medicare tax on wages and salaries. Both levies apply to individuals with income in excess of $200,000 and couples filing jointly with income of $250,000.

Killing The NIIT

Most tax cuts would come by killing the NIIT, which applies to income from capital gains, dividends, royalties, and some annuities. High-income households receive an outsized share of investment income.

The TPC’s distributional analysis excludes premium subsidies, which technically are designed as tax credits but largely function as spending. These subsidies primarily benefit low- and moderate-income households who purchase insurance through the ACA’s marketplaces. Of course, by overturning the law, the Supreme Court not only would end the premium credits, it also would eliminate the health insurance the subsidies support.

The case, Texas v. the United States, was brought by 20 Republican attorneys general. The court is expected to hear oral arguments later this year but it unlikely to rule before the 2020 elections. The Trump Administration has changed is views on the case several times: It initially argued that the courts should throw out only part of the law, but last year reversed course and urged the court to overturn the entire ACA. Last week, faced with a filing deadline at the High Court, Trump said the Justice Department would stick with its call for the Court to scrap the entire law. Repeating a familiar trope, Trump said “Obamacare is a disaster, but we’ve made it barely acceptable.”

One important caveat to the TPC analysis: It was unable to do a formal 10-year revenue estimate since the current and future paths of the economy are so uncertain.

The ACA case will generate enormous interest. And the Court’s decision will affect well over 20 million Americans who have their health insurance through either the ACA health exchanges or expanded state Medicaid programs (it likely will be far more in a wake of the COVID-19 pandemic). But don’t forget, if the Supreme Court accepts the Trump Administration’s argument and throws out the entire ACA, it also will cut taxes significantly for high-income households.