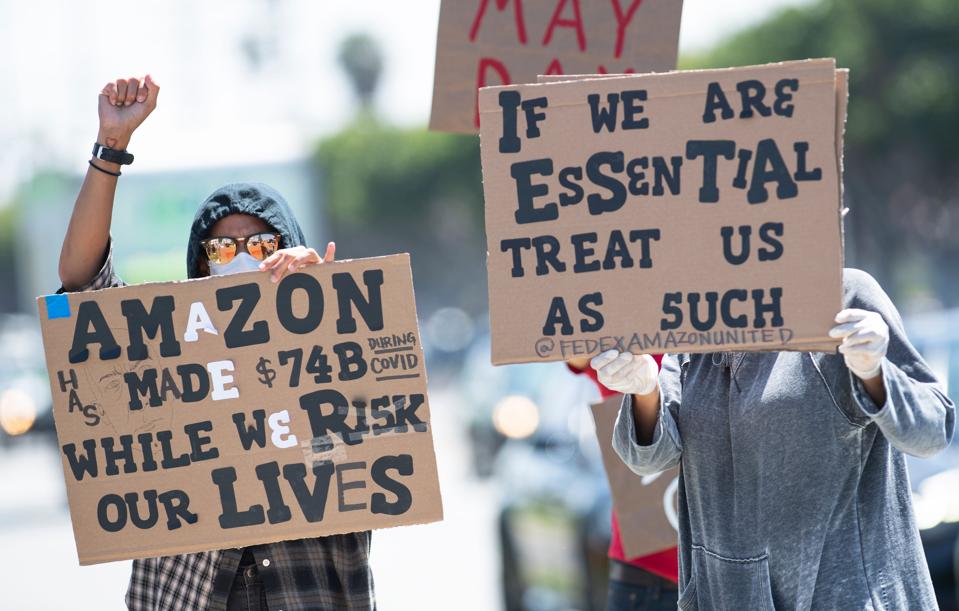

Workers protest (Photo by VALERIE MACON / AFP) (Photo by VALERIE MACON/AFP via Getty Images)

AFP via Getty Images

As the nation the moves into an uncertain and wobbly relationship with the Covid-19 virus, it would be both just and smart to pay more to essential workers for risking their lives in the field. Hazard pay is fair because essential workers’ jobs got worse. It makes economic sense because their jobs just got more valuable.

Hazard pay, sometimes called hardship pay, is not a new idea. The father of modern economics Adam Smith predicted that in truly free markets, where workers competed with employers no more powerful than they, dangerous jobs would pay more than an equivalent safe job.

Pennsylvania Representative Matt Cartwright proposed hazard pay legislation in May. The Coronavirus Frontline Workers Fair Pay Act would make sure that essential jobs pay more. The hike in pay would be capped so that most goes to grocery store workers and nurses, not surgeons. High-risk health care workers would receive a hazard pay increase of $18.50 per hour, and other essential workers would get an extra $13 per hour. Annual additional pay would be capped at $35,000 and $25,000, respectively, meaning some workers would receive up to $2,900 more per month.

Cartwright succeeded in getting a piece of his bill in the HEROES Act, which was passed by House Democrats yet remains stalled in the Senate. The hazard pay part in the HEROES Act would have government pay for the wage boost by establishing a U.S. Treasury Department fund to boost pay for a broad range of essential workers. Although I would prefer that employers footed the bill for the hazard pay, the bill reflects the reality that workers who risk more deserve more.

Labor Power and Hazard Pay

If labor markets had a more equal balance of power between workers and firms, hazard pay would emerge naturally. That’s why, as Annie Lowrey writes, we shouldn’t blame Econ 101 for the low pay of such workers in high demand.

Without something like equal power, workers have to resort to unorthodox measures to fight for what they feel they deserve. For example, Uber and Lyft drivers have circulated an online proposal that would have their companies reduce fees taken from drivers by the companies, liberalize sick leave policies, and pay more for rides in economically hard-hit cities. If these drivers were in a union—or if the federal workplace safety agency wasn’t AWOL on implementing an infectious disease order—the online proposal would be a collective-bargaining demand, not a collective-begging exercise.

Unions help enforce market forces against big employers when safety is at stake. That’s why union technicians working on Toyota Prius hybrid cars bargained for incentive pay for “especially difficult and dangerous” work with dangerously high voltage levels. Even the military must pay a premium to recruit good workers into bad jobs. Private electricians working at U.S. embassy in Afghanistan get 25% of her or his monthly salary in hazard pay. Essential workers exposing themselves to the virus do difficult work with dangerously high virus levels.

Older workers perhaps should get more since they need more sick leave. My graduate student Aida Farmand and I quantified how many older workers are in essential services and their relative lack of paid sick leave. In 2018, 40% of workers aged 50 years and older lacked paid sick days, compared to 38% of workers under age 50. The CDC cites age as an independent risk factor in developing a serious case of Covid-19.

Amazon

AMZN

was forced to boost pay in March in order to keep their terrified workers who were in revolt because of the lack of safety. But Amazon can take the pay increase away anytime. The company could still find willing recruits if some of the millions of unemployed workers lose unemployment insurance and line up ready and desperate to work.

Hazard pay extends the logic of tipping delivery workers extra during the pandemic. Although consumers are somewhat haphazard in their extra tips for Instacart drivers—Steven Greenhouse tells us how dangerous the job is—some of us are willing to tax ourselves in order to award hazard pay to workers. But I have never heard of anyone leaving a twenty dollar bill for the orderly in the ICU.

Essential Businesses Could Pay With Excess Profits

As workers’ jobs get worse in essential sectors, business profits swell in some of the same sectors. Exhibit A is Amazon. Michigan Law Professor Reuven S. Avi-Yonah wants to bring back the excess profits tax. He argues that fighting the virus is not unlike fighting Nazis and proposes an excess profits tax on companies with spiky, above-average profits.

Tech companies like Amazon and Zoom—along with 3M, Gilead, Walmart

WMT

, and even health insurance companies who aren’t paying for elective surgeries and checkups hospitals—are now earning what historians and economists call “excess profits” due to the crisis. These are profits that could be taxed away. World Wars I and II and the Korean War provide historical precedent. In order to avoid companies getting rich from the war, as well as to keep wages and benefits high, the US created an excess profits tax.

The accounting details are in Avi-Yonah’s proposal. One example of the mechanics is Amazon. Take Amazon’s average revenue in years past before the shelter in place orders (which were a wet kiss to mail order houses). Give Amazon a credit for R&D and apply a 95% tax rate to the excess profits. Importantly, the excess profit tax can be reduced by credits for wages.

I am with Professor Avi-Yonah. Have employers pay the hazard pay. They can avoid their excess profit tax by boosting wages, and their profits will go back to something that looks like normal.