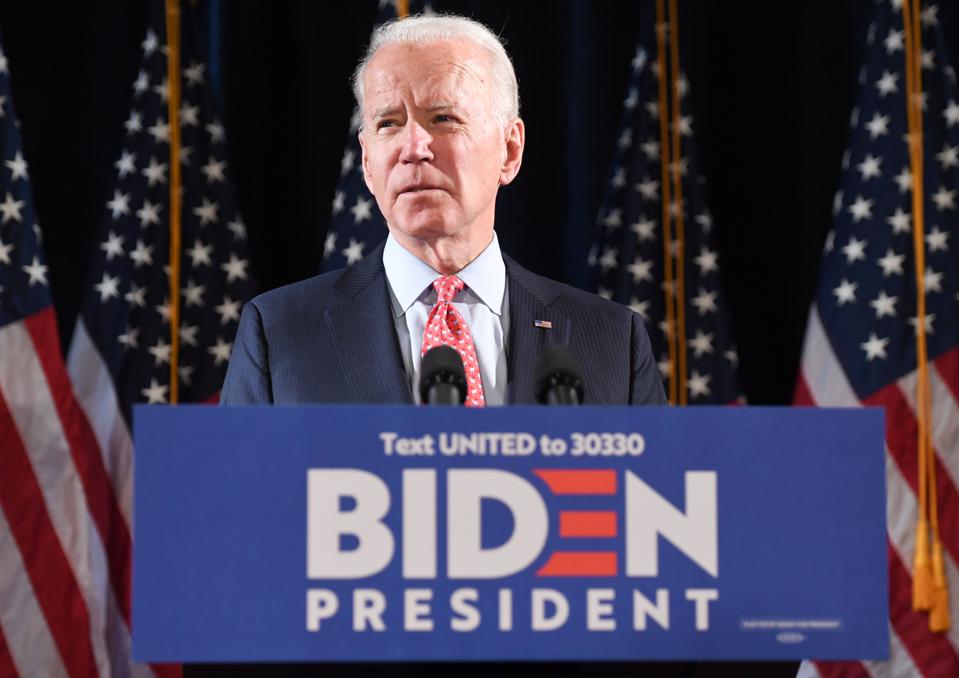

Joe Biden

AFP via Getty Images

Joe Biden’s ambitions seem to be rising with his poll numbers. Victory is anything but certain in far-off November, but Biden isn’t waiting until the game is in the bag. “Biden’s camp is in the disorienting position of scaling up its laundry list of proposals to match the ambition, and the political appetite, he thinks the American people — desperate for relief — will have in January,” reported New York magazine’s Gabriel Debenedetti in a recent look at the campaign’s ongoing transformation.

Every presidential candidate does some on-the-fly planning for his presidency. But the scope of Biden’s current rethinking seems more fundamental than most. Biden has been a fixture on the national stage for nearly half a century, and it’s probably safe to say that few have ever viewed him as a transformational figure on the order of Franklin D. Roosevelt, say, or even Lyndon Johnson. But that’s exactly the mantle Biden is reaching for these days.

“As he faces the general election amid the deepening economic turmoil, the presumptive Democratic nominee is reaching for the legacy of a radical American president: Franklin Delano Roosevelt,” observed Lauren Gambino recently in The Guardian. Indeed, Biden seems to see the nation’s current crisis as bigger than big. “I think it’s probably the biggest challenge in modern history, quite frankly,” he told CNN’s Chris Cuomo last month. “I think it’s going to — it’s going to, I think, it may not dwarf, but eclipse what FDR faced.”

With the help of his advisers, Biden has started charting the course for his own New Deal. He’s even assembled a modern-day version of the FDR “Brains Trust,” now organized under the rubric of Biden’s six “unity task forces.” To some degree, those task forces are an exercise in party repair, designed to heal the wounds left over from the primaries. In particular, they are meant to assure the disappointed supporters of Sens. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., and Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., that progressives will have a seat at the table, both now during the campaign and later in the White House.

However, progressives may have already won the most important battle: the one for Biden’s heart and soul. “He may look like a milquetoast moderate to the activist left and maybe even to you, but the party — and world — has changed so fast that even his primary platform puts him well to the left of Barack Obama in 2008 and, in many ways, left of Hillary Clinton in 2016,” Debenedetti writes in his campaign profile. Biden may be a centrist, but as the party’s center has moved, he’s moved with it. And without much apparent reluctance.

It’s probably safe to say that few have ever viewed Biden as a transformational figure on the order of Franklin D. Roosevelt, say, or even Lyndon Johnson. But that’s exactly the mantle Biden is reaching for these days.

“The blinders have been taken off,” The Guardian quoted Biden as telling supporters during a virtual fundraiser. “Because of this COVID crisis, I think people are realizing, ‘My Lord, look at what is possible. Look at the institutional changes we can make.’”

That enthusiasm from the candidate hasn’t gone unnoticed, and the web is awash in articles explaining just how genuinely liberal Biden has already become. Case in point: a recent article on FiveThirtyEight.com suggesting that Biden might turn out to be “the most liberal president in modern U.S. history.”

This headline, to be sure, is more than a little overwrought: “Modern” is doing an awful lot of work here, narrowing the field to exclude Roosevelt and Johnson from contention. Perhaps that’s reasonable; the New Deal and the Great Society happened a long time ago. But on the other hand, the policy innovations described by those labels are very much alive today — shaping the lives of millions of Americans (for the better) and our long-term fiscal challenges (for the worse).

Still, defensive complaints about Roosevelt and Johnson notwithstanding, it’s plausible that a newly elected President Biden might arrive at the White House with a governing agenda leaning further left than any other American chief executive’s in the last 50 years.

But will that leftward tilt include tax policy? Like everyone else, I’m just guessing, but I suspect the answer is twofold: initially no, but eventually yes.

Biden’s Existing Plan

To date, Biden’s campaign tax plan has been something of a piecemeal affair, released in dribs and drabs over the course of many months, and lacking a central theme beyond (1) a vague commitment to increased progressivity, and (2) a generalized opposition to most elements of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.

In many important ways, Biden seems very much a modern, mainstream Democrat when it comes to tax policy. That is, he begins with a rather modest overall interest in the topic. I’m unsure which Democratic president was the last one to really care about taxation and tax reform, but it might have been John F. Kennedy. (You could make a case for Jimmy Carter, but I’m unconvinced.) At any rate, no Democratic president since Kennedy has spent much political capital on tax reform.

Instead, Democrats for the past 50 years have tended to see taxes as a necessary means to other, more interesting ends. Back in the day, when deficits were still something lawmakers actually worried about, taxes were a way to pay for spending. More recently, Democrats embraced an array of targeted tax expenditures as a way to spend money without actually “spending” money. All the while, they have engaged in a sometimes spirited but often perfunctory rear-guard action against Republican tax cutting. Some of that defensive action has been successful, other parts less so. But at no point has tax policy been a centerpiece of Democratic governance.

Biden’s campaign tax proposals fall generally within this recent Democratic tax tradition. That’s not to say that Biden’s tax plan is small when measured in dollar terms. According to an estimate from the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, his disparate collection of proposals would raise an additional $4 trillion in revenue between fiscal 2021 and fiscal 2030.

One of Biden’s biggest revenue raisers is a proposal to apply the payroll tax to earnings above $400,000 — that alone would raise $962 billion. His plan to increase the corporate income tax rate to 28 percent would raise an additional $1.3 trillion, according to the Tax Policy Center report. Other big hikes: a proposal to treat capital gains and dividends as ordinary income above a $1 million income threshold and to tax unrealized capital gains at death ($448 billion together), and a plan to restore both the pre-TCJA individual income tax rates and the cap on itemized deductions for high-income taxpayers, as well as a plan to phase out the section 199A deduction for qualified business income above $400,000 (another $432 billion).

Democrats for the past 50 years have tended to see taxes as a necessary means to other, more interesting ends.

One number that keeps popping up in these Biden proposals is $400,000 — the income threshold at which Biden is ready to raise taxes on individuals. That number is really quite big — much bigger than the old $250,000 threshold that was kicked around during the Obama years as the line separating the lucky from the unlucky; in 2016 Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders were known to use the same dividing line.

On this question — where to draw the line for tax increases — the new, more progressive Biden sounds very much like the old, more moderate Biden. “Nobody making under 400,000 bucks would have their taxes raised, period,” Biden told CNBC on May 22. (Related coverage: p. 1630.)

Looking Ahead

So far, then, Biden’s progressive reinvention doesn’t seem to be making much headway in the tax department. But these are early days: Biden’s policy-focused task forces aren’t yet even a month old, and it seems churlish to assume that tax will escape their notice entirely.

So let’s engage in some rank speculation. And to keep things honest, we’ll ground it in some history. Biden has suggested that America is confronting something like a wartime crisis — a challenge of monumental scale and severity that will demand much, if not all, of the nation’s communal effort and attention.

In general, I’m dubious about the wartime analogy. (Prior analysis: Tax Notes Federal, Apr. 20, 2020, p. 399.) I think a comparison to the Great Depression, and especially its early years, is altogether more apt.

If Biden wins the election and takes office in January 2021, there’s a decent chance he will confront the worst economic conditions of any new president since Roosevelt. They may not be as bad as the ones Roosevelt himself faced; much depends on the shape and speed of the recovery. But unemployment, at least, seems reasonably likely to remain at a post-World War II high. And if things don’t go well, joblessness may even approach the levels reached during the worst years of the Great Depression.

All of which means that when Biden searches for historical inspiration, he should probably be looking at the start of Roosevelt’s first term in office. When he took the oath of office in March 1933 (Inauguration Day came late back then), Roosevelt faced a nation in free-fall, gripped not simply by joblessness, but by a severe financial crisis — including a terrifying bank run that stretched from late 1932 into the early months of 1933.

In that economic context, tax reform wasn’t at the top of anyone’s list. Nowadays, policymakers often respond to unemployment with tax cuts, but in those pre-Keynesian days, stimulative tax cuts weren’t yet an element of conventional wisdom (assuming that’s a fair description of them today, which may be a bit of an overstatement and oversimplification). In any case, major tax reforms were absent from the early New Deal.

When Biden searches for historical inspiration, he should probably be looking at the start of Roosevelt’s first term in office.

To be sure, the early New Deal included a few significant pieces of tax legislation, notably limitations on loss deductibility for individuals and members of partnerships (included in the National Industrial Recovery Act) and the famous processing tax enacted as part of the Agricultural Adjustment Act (and later invalidated in United States v. Butler, 49 F.2d 52 (5th Cir. 1931)). But those were minor elements of a mammoth legislative agenda, which centered on a host of nontax issues.

But even in these early months, New Deal policymakers were very much thinking about tax. Even when Congress wasn’t passing new tax laws, Treasury officials were working hard to develop laws that should be passed. During the dark days of 1933 and 1934, in particular, Treasury prepared a dramatic and ambitious agenda for progressive tax reform.

Roosevelt unveiled that agenda in 1935, on the eve of his reelection campaign, and it yielded at least two important measures: the so-called Wealth Tax Act of 1935 (which raised a variety of taxes, but especially income and estate taxes paid by the nation’s richest taxpayers) and the undistributed profits tax of 1936, which attempted to revamp the taxation of corporations (unsuccessfully, as it turned out, but not without first upsetting more than a few corporate apple carts).

The point is this: Roosevelt arrived at the White House with no short-term plans for tax reform but with a long-term commitment to revamping the tax system along much more progressive lines. That commitment was animated by the nation’s dire economic straits, and when it finally made its way to Capitol Hill, Roosevelt’s agenda for tax reform drew political strength from those same conditions.

The lesson for the Biden era, I think, is that we should take seriously the ideas of left-leaning policy advisers who are now finding a home in his campaign. It’s hard to say, looking at the members of Biden’s new “economy” working group, exactly where the campaign will land when it comes to tax policy. But it seems more than likely that it will be well to the left of where it began.

For instance, it’s not out of the question that Biden will find room for a wealth tax in his planning, both for the campaign and for his presidency. Such a tax has become a touchstone for progressive activists, and any number of Biden’s primary competitors embraced the idea. More to the point, Sanders embraced it, as did Warren, and Biden needs the support of both Sanders and Warren voters if he hopes to dislodge President Trump from the Oval Office.

Similarly, Roosevelt’s embrace of the payroll tax as a funding mechanism for Social Security might point the way toward healthcare reform. Don’t get me wrong: I think we’re a long way off from either single-payer healthcare (which Biden has pointedly chosen not to embrace) or any sort of broad-based tax that might fund such a universal program (like a VAT). In the short term, I don’t think the payoff (single-payer insurance) is sufficiently appealing to win approval for something deeply unappealing (a regressive and almost certainly substantial tax).

That said, systemic crises have a way of dislodging patterns and bottlenecks. The coronavirus pandemic may not ultimately play that catalytic role, but it’s too soon to rule out the possibility. And if the country begins to move toward single-payer healthcare (or something like it but perhaps less ambitious), then the Roosevelt model — regressive, broad-based taxes used to fund progressive, broad-based benefits — seems like a time-tested model with a better-than-average chance of success in American politics.

All that is just speculation. For the time being, Biden’s tax plan remains fairly tame, at least when compared with those advanced by many of his competitors in the late, great primary campaign of 2019-2020.

It’s hard to say exactly where the Biden campaign will land when it comes to tax policy. But it seems more than likely that it will be well to the left of where it began.

But Biden’s people are hard at work, just like Roosevelt’s people were hard at work, developing a program today for execution tomorrow. One of those advisers, Jared Bernstein, has said as much, indicating that Biden is looking beyond the short-term problems created by the pandemic to the many “structural” issues that make recovery from the pandemic more difficult.

“Biden is, I think, developing a particularly robust agenda that really strikes at this reality that the Trump economy was built on a house of sand and has turned out to be totally non-resilient to any shock,” Bernstein, a senior fellow at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and former chief economist to Biden, told The Guardian.

That’s vague language, pointing toward almost anything — or perhaps nothing at all, at least when it comes to specific policies. But given the way Democrats have been moving these past few years — and Biden’s demonstrated capacity for keeping pace with his party’s shifting agenda — his tax program is probably headed for a progressive overhaul.