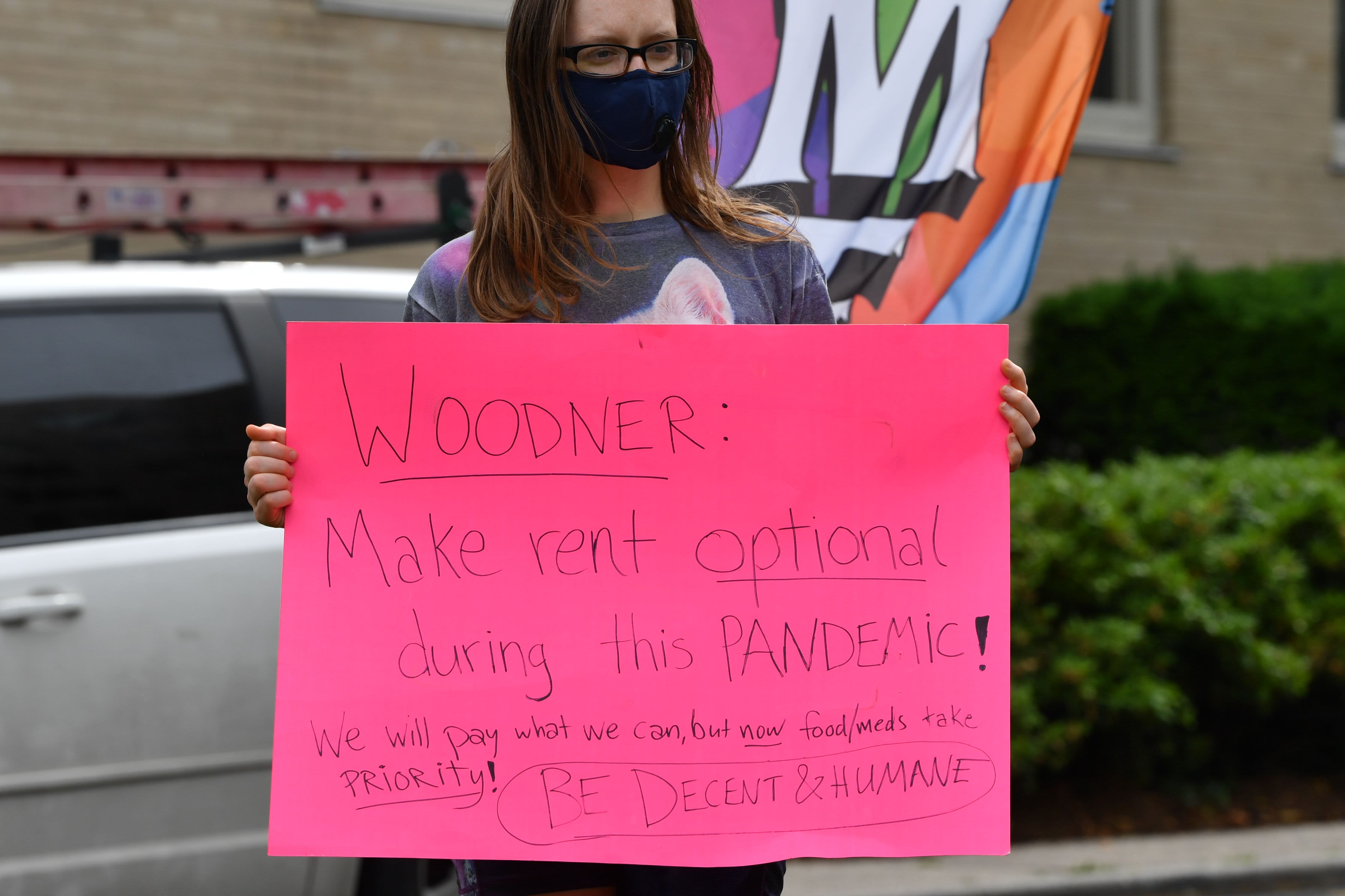

Tenants of the Woodner apartment building in Washington, D.C., protest to demand their rent be forgiven during the Covid-19 pandemic.

NICHOLAS KAMM/AFP via Getty Images

Unemployed workers living in most U.S. cities can’t cover basic living expenses with jobless benefits alone.

In fact, Americans living in just 12 out of 109 metro areas could afford rent, food and transportation with state unemployment insurance, according to a recent analysis published by Clever Real Estate.

That’s largely a result of two factors: high cost of living and the relatively meager generosity of some state unemployment benefits.

Some of the shortfalls were steep.

More from Personal Finance:

Medicare open enrollment is coming up

PayPal, consumer groups battle over company’s credit line for school costs

More than 5 million people won’t get the $300 unemployment boost right now

In San Francisco, which had the largest gap, the typical unemployed worker living in a two-bedroom apartment would need about $3,211 beyond unemployment benefits to afford basic living costs, according to the analysis.

“For the majority of the larger metros in the U.S., people wouldn’t be able to afford just those three things,” Francesca Ortegren, a data scientist at Clever Real Estate, said of rent, food and transportation.

“Unemployment insurance isn’t typically a long-term solution,” she added. “But during a pandemic like this, when it’s uncertain when or if people will be able to get another job soon, these benefits just won’t cover costs of simple living expenses.”

The findings come as about 28 million workers were collecting unemployment benefits in early August, according to most recent data from the Labor Department.

Recipients are no longer getting a $600-a-week federal supplement to unemployment benefits, which expired at the end of July. That has left workers with only their state-allotted aid for almost a month.

On average, states paid $308 a week — or $1,232 a month — in June, according to the Labor Department.

That’s not enough to cover rent in many cases. Renters pay about $791 per month for a studio apartment, $1,004 for a one-bedroom, $1,234 for a two-bedroom, $1,651 for a three-bedroom, and $1,938 for a four-bedroom apartment, according to the Clever Real Estate analysis of fair-market metro-area rents in the U.S.

The typical metro resident also spends about $510 a month on food and $115 on transportation, not including costs like car insurance and gasoline, the analysis found.

Meanwhile, federal eviction protections and similar measures in around 30 states have ended — meaning millions may be kicked out of their home if unable to pay their rent or mortgage.

President Trump signed an executive measure in early August to give workers an extra $300 a week in federal unemployment aid. (States can opt to kick in an extra $100 a week, though most are not.)

However, millions of workers currently don’t have access to that “lost wages assistance.” More than a dozen states have yet to receive federal approval to offer the subsidy and thousands will be left out due to program restrictions on eligibility.

It appears just two of the 32 approved states — Arizona and Texas — have begun disbursing funds to unemployed workers. Workers in many other states will likely be waiting well into September to get the assistance. When the aid arrives, it’s only estimated to cover about five weeks of unemployment.

States have varying degrees of generosity when it comes to unemployment benefits. They set their benefit levels in a range between a minimum and maximum weekly value.

Mississippi, for example, has the lowest maximum of any state, at $235 a week. Massachusetts has the highest: $823 a week, plus an extra $25 for dependents up to a total $1,234 per week.

Benefit levels don’t fully correspond with a state’s cost of living, according to economists.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, unemployment benefits go furthest in two Massachusetts cities — Springfield and Worcester.

California cities — San Francisco, San Jose and Oakland — claimed the three bottom spots relative to affordability. The state pays “middle of the road” benefits and has high cost of living metro areas, according to Ortegren.