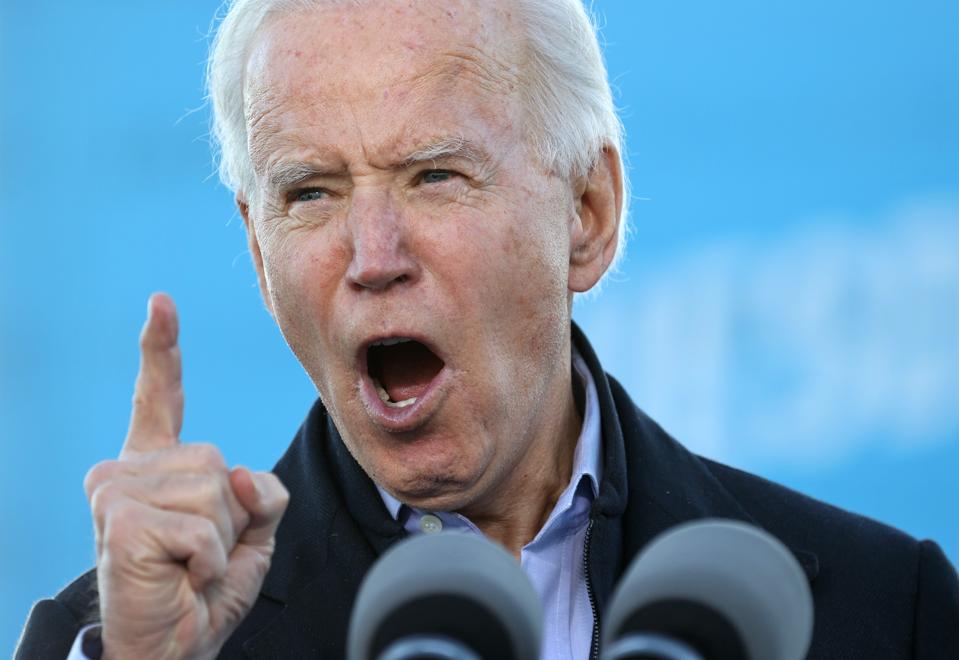

ATLANTA, GEORGIA – JANUARY 04: President-elect Joe Biden speaks during a campaign rally with … [+]

Getty Images

Joe Biden believes in making deals. Indeed, he made it a cornerstone of his presidential campaign. “Compromise is not a dirty word,” he said in a July speech to the National Education Association. “It’s how our government is designed to work.”

Biden has some real experience to put behind those words: After winning his first election to the Senate in 1972, he went on to broker a long string of legislative compromises, ranging from the 1994 crime bill to the Iraq war vote. And his dealmaking didn’t stop when he left Capitol Hill for the vice president’s mansion in 2009. At several critical junctures, President Obama asked him to run point on sensitive congressional negotiations. “He has from the beginning been an über liaison to his former colleagues,” a White House aide told The New York Times

NYT

in 2010.

Biden hammered out some very big deals for the Obama administration, including the 2009 stimulus legislation and a pair of crucial tax compromises in 2010 and 2012. Not all of Biden’s fellow Democrats, however, were happy with those deals.

His former colleagues in the Senate were especially unhappy with Biden’s 2012 compromise, which they considered an unnecessary gift to Republicans — and an unforced error for Democrats.

It’s worth revisiting these Biden tax deals, both of which focused on the extension of President George W. Bush’s signature tax cuts. Both managed to irritate at least some of Biden’s Democratic colleagues. And both raised questions, then and now, about Biden’s skill at cutting a deal — or at least his skill at cutting a good one.

Deal One

The November 2010 midterms were a disaster for Democrats. Republicans won 63 seats in the House, giving them a 242-193 majority. In the Senate, the GOP gained seven seats, leaving the party still short of a majority but dramatically shrinking the Democrats’ advantage in the chamber.

MORE FOR YOU

In the weeks after the election, lawmakers turned to various pressing issues, including the expiration of the Bush tax cuts, slated to expire at the end of the year. Obama had begun negotiations with congressional Republicans by arguing that cuts should be extended only for taxpayers earning less than $250,000 annually. The Democrats’ lame-duck majority in the House passed a measure doing just that, but Republicans blocked similar legislation in the Senate.

As lawmakers from both parties squared off, Obama dispatched Biden for a round of secret negotiations with Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell. Each brought a single staffer to a series of clandestine meetings in the vice president’s ceremonial office on Capitol Hill. (Biden, incidentally, brought along his vice presidential chief of staff, Ron Klain, now slated to be chief of staff in Biden’s presidential administration.)

Senate Majority Leader Senator Mitch McConnell (R-KY) and US Vice President Joseph R. Biden(R) … [+]

AFP via Getty Images

Ultimately, Biden emerged from these meetings with a deal. “It was a bipartisan bargain that, in a startling departure from the past two years in the capital, ended with Republicans praising it and Democrats claiming they were blindsided and undercut,” The New York Times reported at the time.

Indeed, the deal gave Republicans much of what they wanted, including a two-year extension of the Bush income tax cuts for all taxpayers, regardless of income.

Biden also agreed to a return of the recently lapsed estate tax, now outfitted with a $5 million exemption and a top rate of 35%. These parameters were a disappointment to many Democrats, since absent any deal, the tax would have returned with a $1 million exemption and a 55% top rate.

In exchange for those concessions, the deal allowed Obama to dodge a bullet: wholesale expiration of the Bush tax cuts, which might have derailed the fragile economic recovery. Obama also got roughly $300 billion in new economic stimulus, including a one-year, 2 percentage point cut in the Social Security payroll tax, an extension of unemployment benefits, and the extension of various tax credits for lower-income taxpayers.

Obama defended Biden’s compromise as a practical necessity. “We have to find consensus here because a middle-class tax hike would be very tough not only on working families, it would also be a drag on our economy at this moment,” he said.

“We’ve got to make sure we’re coming up with a solution, even if it’s not 100 percent of what I want or what the Republicans want.”

Still, Obama voiced some bitterness at the terms of the deal. “What is abundantly clear to everybody in this town is that the Republicans will block a permanent tax cut for the middle class unless they also get a permanent tax cut for the wealthiest Americans,” he said.

Many Democrats on Capitol Hill were unconvinced by Obama’s defense of the compromise, insisting that Biden had gotten a bad deal from McConnell. For what it’s worth, McConnell seemed to share that opinion.

“As far as Republicans were concerned, the deal was terrific, as evidenced by the fact that come the day of the bill signing, I attended, while [Senate Majority Leader] Harry Reid and [House Speaker] Nancy Pelosi were conspicuously absent,” he recalled in his memoir.

Deal Two

In late 2012 Biden negotiated a second major tax deal. This time, Democrats were coming off a big victory in the presidential election, with Obama comfortably defeating Mitt Romney. On Capitol Hill, the status quo reigned, with Democrats maintaining control of the Senate and Republicans keeping their House majority.

Once again, the Bush tax cuts were coming due. And this time, Democratic leaders were determined to let them expire completely. The resulting revenue windfall would immediately shift the terms of debate, they contended:

If they simply waited until the start of 2013, they could use that revenue for their own round of tax cuts, rather than being forced to use the Bush tax cuts as a starting point.

“I wanted to go over the cliff,” Reid later explained to Ryan Grim of The Intercept. “I thought that would have been the best thing to do because the conversation would not have been about raising taxes, which it became; it would have been about lowering taxes.”

Once again, however, Biden stepped in to save the day — for McConnell. Acting again at Obama’s behest, Biden negotiated a compromise with Republicans to extend the Bush tax cuts. And rather than extending them only for those earning less than $250,000 annually (Obama’s long-stated preference), Biden agreed to set the figure at $450,000 in annual income.

Republicans also agreed to a one-year extension of unemployment benefits.

Many Democrats were livid — not simply at the generous treatment of wealthy taxpayers, but at the missed opportunity to set Republicans on their heels.

“The deal with Mitch McConnell was a complete victory for the Tea Party,” complained Sen. Michael F. Bennet, D-Colo., during a Democratic primary debate in June 2019. “We had been running against this for 10 years. We lost that economic argument because that deal extended almost all those Bush tax cuts permanently and put in place the mindless cuts we still are dealing with today that are called the sequester.”

WASHINGTON, DC – MAY 05: Sen. Michael Bennet, D-Colo., right, speaks during a Senate Intelligence … [+]

Getty Images

Bennet was scornful of Biden’s attempt to claim credit for the 2012 deal. “That was a great deal for Mitch McConnell and a terrible deal for America,” he said.

Good Deals and Bad

Dealmaking is definitely a useful skill in Washington — at least for anyone interested in passing legislation.

These days, of course, many lawmakers seem only vaguely interested in actually making law. Most seem focused on the performative aspects of legislative politics. (This probably describes a majority of senators from both parties at this point.)

Still, there are a few practitioners of the old arts still kicking around, and Biden is one of them. People poke fun at his dealmaking, but they offer some grudging respect, too.

Michelle Cottle of The Daily Beast captured the attitude well in the middle of the 2012 fiscal negotiations: “Laugh at him all you want. But even Republicans know that when the going gets tough, the tough get Joe.”

Indeed they do. But maybe Republicans “get Joe” because they know that they can also roll him pretty easily.

It’s possible to defend the tax negotiations of 2010 and 2012. Obama and his supporters, for instance, have argued that the 2010 bargain was a decent result, especially given the party’s weak position after the midterm losses.

They have also suggested that its stimulus component may have bolstered Obama’s reelection bid. As for 2012, Biden himself has argued that it was a victory, too — a successful effort to make Republicans agree to major tax increases. “I got Mitch McConnell to raise taxes $600 billion,” he said in that June debate with Bennet.

Of course, the tax increase would have been bigger if Biden had simply done nothing and allowed the Bush tax cuts to expire completely. That point lies at the heart of the Democratic complaint about Biden’s penchant for dealmaking.

If we accept the proposition that the tax deals of 2010 and 2012 were failures (from a Democratic perspective), is it fair to blame Biden for brokering them?

After all, he was working for Obama, whose evident eagerness to make a deal can’t have made negotiations easy.

Still, both agreements raise legitimate questions about Biden’s negotiating skill. After all, deals are a good thing — but only when they’re good deals.