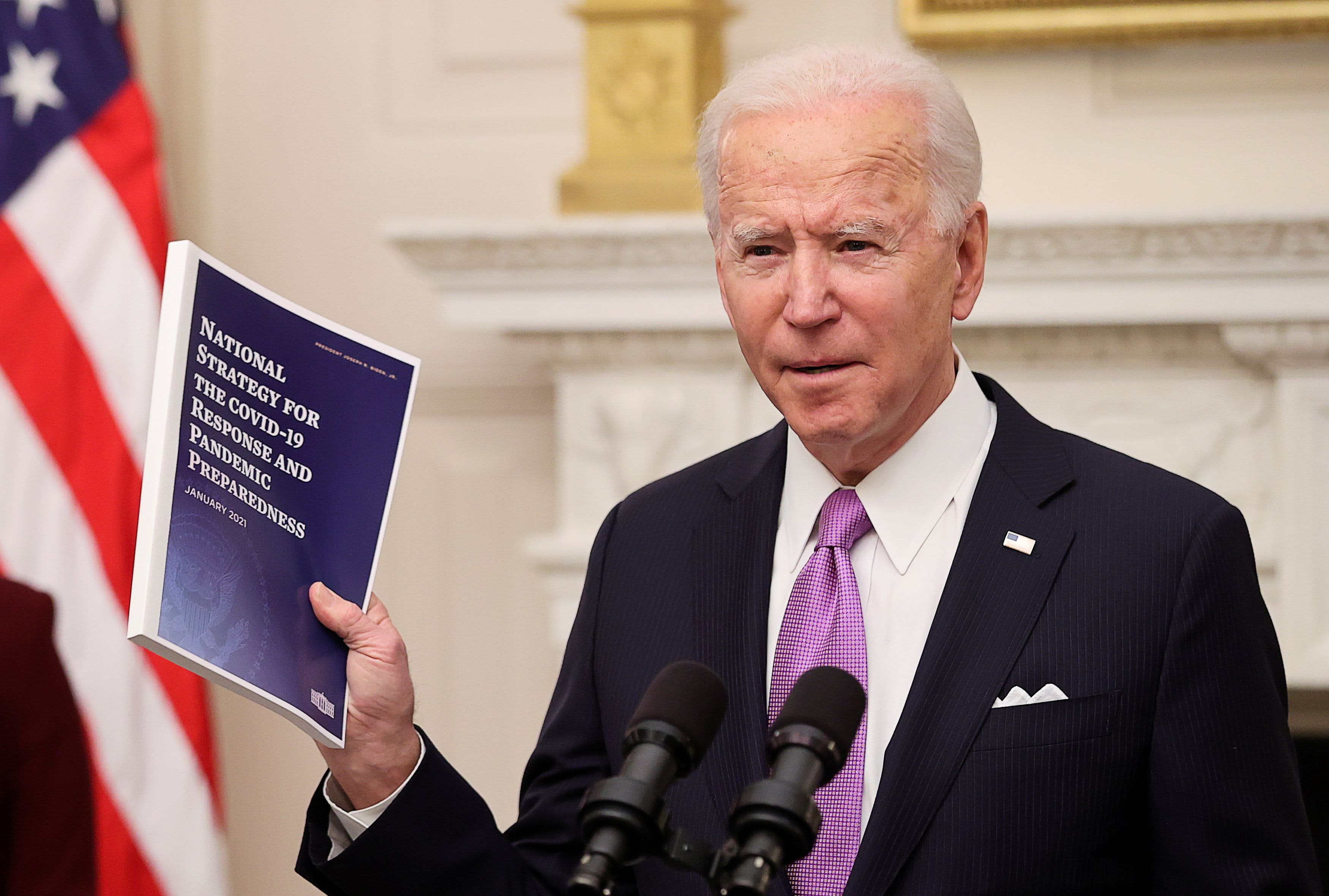

U.S. President Joe Biden speaks about his administration’s plans to fight the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic during a COVID-19 response event at the White House in Washington, January 21, 2021.

Jonathan Ernst | Reuters

Newly elected President Joe Biden has a tall list of priorities in his first days in office, with stemming the pandemic chief among them.

But experts expect one issue he promised to deal with during his campaign, Social Security reform, could also become a focal point as soon as this year.

Millions of Americans count on Social Security benefits to provide income when they are retired or disabled, or when loved ones pass away.

The program’s funds have been running low. The latest official estimate from the Social Security Administration shows that just 79% of promised benefits will be payable in 2035 due to depletion of its trust funds. That estimate does not factor in the effects of the pandemic, which experts say could move that date up even sooner.

More from Personal Finance:

How to apply for the $25 billion in rental assistance

Biden is boosting food benefits even more for the most vulnerable

These colleges went to remote learning but hiked tuition anyway

Biden touted big changes to the program on the campaign trail.

Under his plan, eligible workers would get a guaranteed minimum benefit equal to at least 125% of the federal poverty level. People who have received benefits for at least 20 years would get a 5% bump. Widows and widowers would receive about 20% more per month.

Biden also proposes changing the measurement for annual cost-of-living increases to the Consumer Price Index for the Elderly, or CPI-E, which could more closely track the expenses retirees face.

To pay for those higher benefits, Biden would apply Social Security payroll taxes to those making $400,000 and up. In 2021, workers generally pay the 6.2% Social Security tax on up to $142,800 of wages. (Earnings between $142,800 and $400,000 would not be subject to those levies under the plan, though that gap would eventually close over time.)

Other Democratic candidates in the run-up to the 2020 presidential election also issued their own ideas for Social Security reform. The last time sweeping changes were put in place was in 1983, when then President Ronald Reagan, a Republican, struck a deal with Democratic House Speaker Tip O’Neill, D-Mass.

“I’ve always believed it takes a Democratic president to do Social Security reform,” said Jason Fichtner, a fellow at the Bipartisan Policy Center and former Social Security Administration official.

Because Biden, 78, has hinted from the outset that he plans to be a one-term president, he would have to address the issue in the next few years.

“I am hoping that President Biden might look at least after the midterms in 2020, going into 2023, of trying to secure a legacy for himself and that would be Social Security reform,” Fichtner said.

What changes could come in 2021

zimmytws | iStock | Getty Images

Experts expect one Social Security issue to be on lawmakers’ agendas this year.

The Covid-19 pandemic has created a so-called notch that would reduce benefits for those turning 62 and claim retirement benefits in 2022, as well as those who file for disability or survivor benefits that year.

Congress is expected to act to prevent those reductions before they take effect.

Because those benefit reductions were directly caused by Covid-19, it could be addressed in the next relief package, said Dan Adcock, director of government relations and policy the National Committee to Preserve Social Security and Medicare.

“I think that’s the most likely early action on Social Security,” Adcock said.

If reduced benefits for that cohort is not included in that upcoming legislation, lawmakers could consider it later in the year, which could prompt bigger conversations about Social Security reform, said Nancy Altman, president of Social Security Works, which advocates for Social Security expansion.

“If it’s not done in the Covid package, then it would make sense to do it in a comprehensive Social Security package, which gives some impetus to acting on it in this coming year,” Altman said.

Room for compromise?

(L-R) U.S. Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) looks on as Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) speaks during a Congressional Gold Medal ceremony at the U.S. Capitol on January 15, 2020 in Washington, DC.

Drew Angerer | Getty Images

Despite a Democratic majority in the House and Senate, there could be obstacles to getting major Social Security reform approved.

Democrats have proposed their own legislation aimed at shoring up the program. The Social Security 2100 Act, proposed by Rep. John Larson, D-Conn., aims to boost benefits and restore the program’s solvency for the next 75 years by raising payroll taxes.

Another proposal, the Social Security Expansion Act, from Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., also aims to increase benefits for low earners while raising taxes for those with higher wages.

In a statement, Larson said the Biden administration, and members of the Senate and House, are looking to come to a consensus by holding roundtables and evaluating different proposals.

“There are a lot of similarities between the Social Security 2100 Act and President Biden’s campaign proposal,” Larson said. “We will be reintroducing a modified Social Security 2100 Act based on what comes out these discussions.”

Meanwhile, on the Republican side, Sen. Mitt Romney, R-Utah, has touted the TRUST Act, which would let lawmakers form bipartisan committees to address programs like Social Security that face a shortfall in funding and fast track changes to improve them.

Traditional Senate negotiations would need bipartisan support, however.

It’s America’s favorite entitlement program, and part of the reason it’s so popular is it’s not solvent.

Rachel Greszler

research fellow at the Heritage Foundation

“It will require 60 votes in the Senate, which means that we have to persuade probably at least 10 Republican Senators to go along with a comprehensive Social Security reform bill,” Adcock said.

Conservative politicians would likely object to raising benefits across the board, said Rachel Greszler, research fellow at the Heritage Foundation.

“There could be room for a compromise to be made here in terms of boosting the minimum benefit that’s provided, so it’s at least at the poverty level,” Greszler said. “But that would have to come … with a reduction in benefits at the top.”

One challenge that could emerge in the negotiations is for leaders to face the decision of whether Social Security should be an anti-poverty or entitlement program, Greszler said. Heritage is advocating for a universal benefit to protect those who are low income, while reducing how much middle- to high-wage earners rely on benefits.

“It’s America’s favorite entitlement program, and part of the reason it’s so popular is it’s not solvent,” Greszler said.

However, groups like Social Security Works and the National Committee to Preserve Social Security and Medicare are focused on preventing benefit cuts.

Some Republicans could be swayed, Altman said.

“Even though the Republicans can try to block it, this is something that’s going to be quite popular with their constituents,” she said. “It’s just a question of whether they’ll do it.”