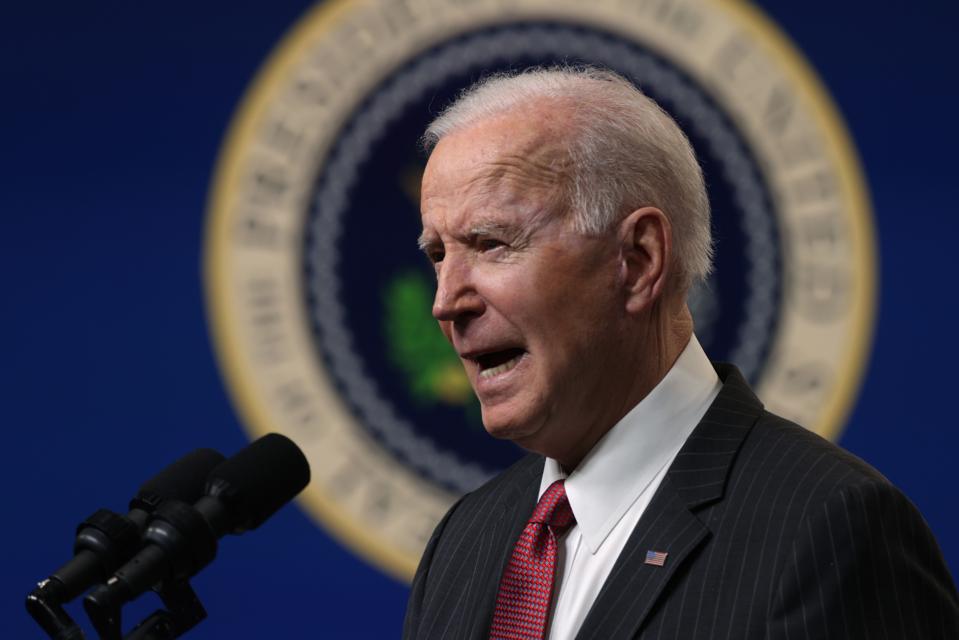

WASHINGTON, DC – FEBRUARY 10: U.S. President Joe Biden speaks as he makes a statement at the South … [+]

Getty Images

President Biden wants to revamp the taxation of capital gains, but if history is any guide, it won’t be easy. The tax preference for capital gains turns 100 this year, making it nearly as old as the income tax itself. And while the preference has been revised and reformed many times, it’s survived nearly every attempt at outright repeal.

Only once have lawmakers agreed to eliminate it entirely — and then only briefly, rethinking their boldness after a three-year experiment.

Biden’s proposal to narrow the preference stops well short of full repeal. As a candidate, he promised to increase the rate for individual long-term gains from 20% to his proposed top rate on ordinary income of 39.6%. That new rate for capital gains would apply only to taxpayers earning more than $1 million a year.

Biden’s effort to target his reform at the nation’s wealthiest taxpayers may change the politics of capital gains reform. But for a century, almost every debate over the capital gains preference has put wealthy taxpayers front and center — and still the preference has survived.

However, the preference’s impressive durability doesn’t seem to provide much solace to taxpayers worried about Biden’s proposal; a quick Google search will deliver scores of articles counseling taxpayers on ways to prepare for the threatened apocalypse.

But the history should be encouraging, at least if you’re a fan of the preference. It should also be sobering if you’re eager to see the preference disappear.

Because one thing is clear: It’s not just the preference that’s old — so are the arguments used to defend and attack it.

MORE FOR YOU

As we stand on the precipice of yet another capital gains debate, we’re also poised to rehash those ancient arguments. Not similar arguments: the exact same arguments, articulated in nearly identical language. It’s enough to shake your faith in progress — or perhaps the advance of time itself. It’s like Groundhog Day for tax.

This article considers the creation of the capital gains preference in the 1920s, focusing on the arguments used to advance it during the moment of its creation.

The Origins

In the beginning, the U.S. federal income tax took no notice of capital gains. The earliest income taxes — the one implemented during the Civil War and the one enacted in 1894 and struck down in 1895 — included no special treatment for capital gains.

More important, the first revenue law enacted after ratification of the 16th Amendment took a similar approach; the Revenue Act of 1913 treated all gains from the sale of property as regular income, taxing them at the same rates as other forms of income. Or at least it seemed to: The absence of specific provisions allowed Treasury to interpret the law that way.

Still, as legal historian Marjorie E. Kornhauser has pointed out, the story is not quite as simple as it might appear. “The standard view of capital gains is that they have always been taxable under the sixteenth amendment and the statutes enacted under it,” Kornhauser wrote in her important article on the topic (“The Origins of Capital Gains Taxation: What’s Law Got to Do With It?” 39 Sw. L.J. 869 (1985)). “This view distorts reality. Although every statute since the sixteenth amendment has taxed gains from dealings in property, that these taxable gains included profits from the occasional sale of property outside the normal course of business was not clear at the outset.”

Indeed, tax experts of the early 20th century were open to the idea that capital gains might deserve special treatment.

“Some economic theorists and lawmakers had been advocating for specific classifications of income well before the income tax became law,” observed Ajay K. Mehrotra and Julia C. Ott in their fascinating study of this period (“The Curious Beginnings of the Capital Gains Tax Preference,” 84 Fordham L. Rev. 2517 (2016)).

But the key figures in Congress were wary of complicating things too much, especially as taxpayers were struggling to make sense of the new fiscal regime.

In early 1921, after a challenge from hopeful taxpayers, the Supreme Court clarified matters, deciding a series of cases that largely settled arguments over the status of capital gains under the income tax.

WASHINGTON, D.C. – APRIL 19, 2018: The U.S. Supreme Court Building in Washington, D.C., is the seat … [+]

Getty Images

In Merchants’ Loan & Trust Co. v. Smietanka, 255 U.S. 509 (1921), the Court held that gains from the one-time sale of property were indeed taxable as regular income.

Postwar Tax Relief

The Supreme Court decisions lit a fire under lawmakers — not that it needed much kindling. Between 1913 and 1918, the top marginal rate on individual income had soared from 7% to 77%, thanks to the fiscal demands of World War I.

After the war, with the nation mired in an economic slump, lawmakers were determined to slash the federal tax burden. While many levies were on the chopping block (including taxes on corporate income), individual rates were a special target, if only because they had risen so high and so quickly. With the Court’s clarification that these rates would apply to capital gains, the imperative to reduce them was intense.

As part of its 1921 tax relief legislation, the Republican majority on Capitol Hill agreed to significant rate reductions for the individual income tax. Lawmakers also agreed, however, on a new rate preference for capital gains, establishing a flat 12.5% rate for capital assets held for at least two years. By contrast, they set the top marginal rate for other forms of income at 66%.

Supporters defended this large rate differential in terms that modern-day fans of the capital gains preference will find familiar. In describing the 1921 debate, Mehrotra and Ott focused on the congressional testimony of Fredrick R. Kellogg

K

, a prominent corporate lawyer of the day.

“In defending his proposal, Kellogg articulated many of the rationales that defenders of the capital gains preference would repeat down to the present day,” Mehrotra and Ott wrote. “Unless granted a preferential rate, Kellogg claimed, capital gains taxes unfairly burdened the average property owner, who might realize one large gain in his lifetime only to see it eaten up by the government when that windfall bumped him into a higher income tax bracket in the year of sale. Income from capital gains also deserved preferential treatment because inflation reduced the real value of capital gains, even before taxes were paid.”

In another familiar argument, supporters predicted that the lower rate would actually increase revenue by encouraging taxpayers to realize their gains.

“It has been the opinion of all of the experts of the Treasury that the ultimate working out of this would bring more revenue into the Treasury,” declared Republican Rep. William Green of Iowa.

In those comments from a century ago, we see the precursors of our modern debate; arguments about “bunching,” “lock-in,” and inflation — all fixtures of today’s capital gains debate — are as old as the preference itself.

As Mehrotra and Ott chronicled, Kellogg warned lawmakers about investors who refused to sell stocks, afraid to realize their gains, only to see them evaporate when markets tanked; of average homeowners forced to sell their homes in the face of a job loss, only to face ruinous tax bills adding to their woes; and of capital “frozen” in unproductive investments, impeding reinvestment in the “fluid” fashion that a healthy economy required.

“What is perhaps most interesting about the 1921 origins of the capital gains tax preference is how the present-day justifications for the tax benefit were also there at its beginnings,” Mehrotra and Ott concluded.

Another Preference

The 12.5% capital gains rate preference remained unchanged throughout the 1920s.

Those years were good ones for Republicans and their tax priorities, and while Democrats found traction for some of their fiscal complaints, the capital gains preference faced no serious threat during the decade.

In 1924, however, lawmakers agreed to create a second, parallel preference that raised questions — albeit implicit — about the fairness of the capital gains preference.

At the behest of Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon, one of the nation’s richest men and a champion of low taxes on investment income, lawmakers enacted a special break for earned income relative to unearned income.

(Eingeschränkte Rechte für bestimmte redaktionelle Kunden in Deutschland. Limited rights for … [+]

ullstein bild via Getty Images

Mellon made the case for this new preference in Taxation: The People’s Business (1924), his brief but popular (or brief and therefore popular) book on tax policy. “The fairness of taxing more lightly income from wages, salaries or from investments is beyond question,” Mellon wrote. “In the first case, the income is uncertain and limited in duration; sickness or death destroys it and old age diminishes it; in the other, the source of income continues; the income may be disposed of during a man’s life and it descends to his heirs.”

Such comments may seem surprising coming from someone like Mellon — not least because he was notably inconsistent on this point.

On the very next page after calling for his new tax preference for labor income, Mellon suggested that capital gains should be entirely exempt from taxation. “It would be sounder taxation policy generally not to recognize either capital gain or capital loss for purposes of income tax,” he wrote.

To some degree, Mellon’s inconsistency may have been more apparent than actual. He never made his reasoning especially clear, but he seemed to believe that income from investments meant income from interest and dividends.

Capital gains, by contrast, weren’t actually income at all, at least to him. (Mellon pointed out that many other countries took this view of capital gains in structuring their own tax systems.)

Whether or not Mellon was being inconsistent, his proposal to create a tax break for labor income bore directly on the arguments supporting the capital gains preference, then just three years old.

“Because the tax code already had provided a lower rate for capital gains, it was only fair, or so the argument was made, that a tax benefit also be granted to labor income,” Mehrotra and Ott wrote. The argument persuaded lawmakers to establish a 12.5% preferential rate for the first $10,000 in income above the personal exemption, categorizing that income as “earned.”

Given the narrow scope of the individual income tax in the mid-1920s, this preference was of limited benefit to most Americans. It was not a benefit for the working class, since the working class didn’t pay income taxes in the first place; it was really a preference for the labor of hardworking lawyers, accountants, and doctors.

Still, the credit represented an important recognition that earned income deserved a break — in no small part because capital income already had one.

Old Arguments

The 1920s brought forth not simply the capital gains preference but also a set of arguments to defend it. Both the preference and the arguments have survived to the present day.

And while the preference has undergone substantial change over time, the arguments have stayed largely consistent, focused on issues of lock-in, bunching, and inflation. Having served well as justification for creating the preference, they have also protected it during the later decades.

But during the first decade of existence, the capital gains preference didn’t need much protecting. It seemed to be broadly popular, or at least broadly tolerated; in any case, the Republican political ascendancy of the 1920s made it hard to challenge.

But even in those years of its greatest security, the preference gave rise to an implicit challenge in the form of a second preference. The creation of the earned income preference in 1924 raised an issue of fairness that would increasingly threaten the capital gains preference, if only indirectly.

If progressive activists today are eager to “tax wealth like work,” it’s important to bear in mind that Mellon was framing issues in similar terms in 1924. We shouldn’t overstate the similarities: Mellon was no champion of progressive tax reform — far from it.

But he was toying with ideas that were more powerful — and perhaps more dangerous to his broader conservative tax program — than he realized at the time.

Tax experts would soon bolster their critique of the preference, and by the 1930s, it would be under direct attack from New Deal officials. While not rejecting the traditional arguments for the preference, those critics would counter them with fairness arguments that they considered more powerful.