Virtual currency is one of the few success stories of 2020. In March of 2020 Bitcoin was around $4,000 per Bitcoin, and by December 2020 it was up to just below $30,000 per Bitcoin. Investors and market watchers were not the only ones paying attention to the meteoric rise of virtual currency – the Department of Treasury and FinCen have also been watching and planning for changes in virtual currency reporting requirements.

KATWIJK, NETHERLANDS – FEBRUARY 20: In this photo illustration, one-ounce silver American Eagle … [+]

Getty Images

Reporting Virtual Currency on IRS Form 1040 (Your Tax Return).

Think you can keep your interest in virtual currency to yourself? Think again.

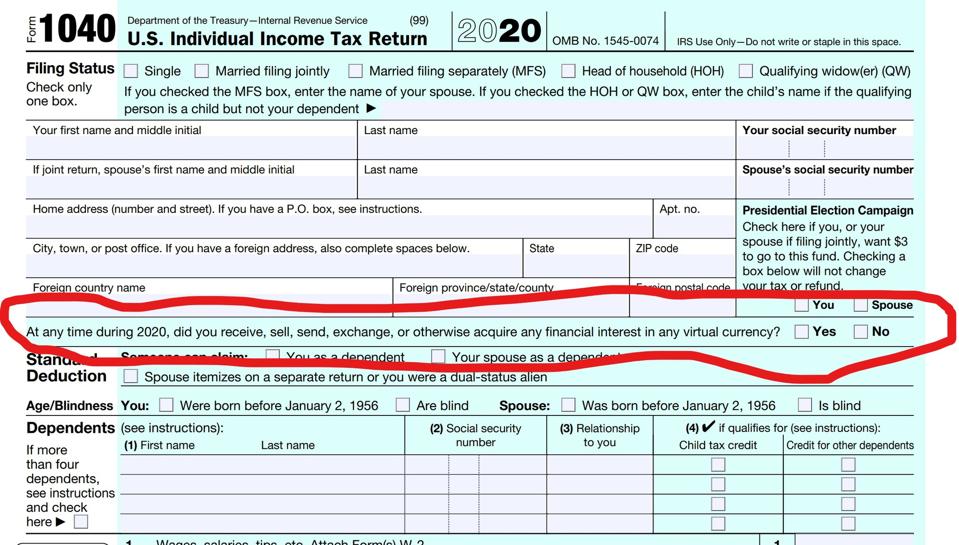

The Treasury Department has issued the 2020 IRS Form 1040, U.S. Individual Income Tax Return for 2020, which looks a little different this year:

The 2020 IRS Form 1040 requires taxpayers to answer whether they have received, sold, sent, … [+]

2020 IRS Form 1040 snip

Parents, if your children have the ability to access a computer, do yourself a favor. Before you file your tax return, ask your children whether they bought, sold, exchanged, or otherwise acquired an interest in virtual currency last year. I presented on taxation of virtual currency at the IRS Nationwide Tax Forum in 2019, and after my presentation, I had a line 40+ long of return preparers who had the same question for me: What do I do about the parents who filed returns but had no idea that the kids had Bitcoin? The answer varies depending on the circumstances, but the short answer is the same: if the error or omission was not intentional, whenever possible, it is almost always better to let the IRS know before an audit or exam gets underway.

For those who have invested in virtual currency themselves, for 2020 the obligation to report that interest could not be more clear. The importance that the IRS places on reporting virtual currency transactions can’t be overstated – indeed, it ranks so high that the IRS has placed the question regarding any transaction regarding virtual currency on page one of Form 1040.

MORE FOR YOU

The IRS has clearly learned from past mistakes – like putting the question about whether a taxpayer has a financial interest or signature authority over a foreign financial account on the bottom of Schedule B. Back in 2008, taxpayers who looked very closely at the bottom of Schedule B would have seen this:

2008 IRS Form Schedule B Part III

GMM

Lots and lots of taxpayers – not surprisingly – missed the question entirely. People failed to report their foreign bank accounts both on their tax returns and their Report of Foreign Bank and Financial Accounts (FBAR). Some taxpayers actually did not see the question on Schedule B and made an honest mistake, while others intentionally omitted any reference to their foreign accounts.

Now, with the question about whether a taxpayer received, sold, bought, or otherwise exchanged virtual currency just below the taxpayer’s name, neither taxpayers nor the IRS should expect anyone who fails to accurately answer that question to argue that they didn’t know they were required to tell the IRS about crypto.

FBARs Are Not Just For Bank Accounts Anymore

On December 30, 2020, when most people were contemplating the end of the year that never seemed to end, FinCen issued Notice 2020-2, which was short and sweet:

Before FinCen issues any amended regulations making virtual currency reportable on an FBAR, the FBAR should be changed. The current format of the FBAR does not contemplate virtual currency and is not conducive to reporting that kind of asset. Indeed, the IRS has clearly stated that virtual currency is property, and property generally does not need to be reported on an FBAR. Instead, the FBAR is written to accommodate information regarding financial accounts and asks for things like a bank name, address, the type of account, account number, and maximum value of the account during the tax year. The instructions require taxpayers to convert the maximum value by taking the highest value in the account during the tax year and then convert to U.S. dollars by using the exchange rate as of the last day of the year.

You read that right. To determine the maximum value of an account that must be reported on an FBAR, take the highest balance in the account during the year and then convert to Treasury’s Financial Management Service rate (http://www.fms.treas.gov/intn.html) for the last day of the calendar year.

Virtual currency, however, is incredibly volatile. There are many different kinds of virtual currency. Virtual currency that is traded on a foreign exchange is just as volatile, and prices can have a $5,000 or more swing in one day.

Rather than try to squeeze a square peg into a round hole, if the government is serious about requiring U.S. taxpayers who own virtual currency on a foreign exchange, or otherwise considered to be in a foreign country, the FBAR should be revised to allow taxpayers to report their virtual currency in a way that both makes sense and provides the government relevant data. For example, asking about the name of the currency and how many units are owned would be both simpler to report for the taxpayer and more informative for the government.

Penalties for Getting it Wrong

Penalties for mistakes on a tax return can be anywhere from 20 percent to 75 percent of the understatement of tax. Not all virtual currency transactions have tax implications. And the question on page one about virtual currency has no tax implications. Receiving virtual currency as income, mining, selling, or otherwise exchanging virtial currency will have tax implications. So why is the government asking that question? A few reasons. First, a taxpayer who should have reported the income or sale of virtual currency who does not won’t be able to argue ignorance when it comes to the reporting requirement. A page one question puts the taxpayer on notice as to the issue generally. Second, the IRS may use an incorrect answer to that question to assert the 75 percent fraud penalty on any tax that is due, arguing that anyone who answers a simple yes or no question incorrectly could only have one reason: fraudulent concealment. Finally, the IRS may argue that answering the virtual currency question incorrectly has statute of limitations implications.

When it comes to the FBAR, the penalties are even more punative. Assume Jenny has 6 Bitcoin should bought in December of 2019 at $3,000 per Bitcoin*. She keeps her virtual currency on a foreign exchange. In 2021, she sells one Bitcoin on February 23 for $48,899.90. Assume Jenny lost her job in 2020 and has no other income in 2021, and assume regulations have changed requiring reporting of virtual currency on a foreign exchange on an FBAR.

Jenny should report a gain of $45,899.90, and it is long-term because she has had the asset for longer than one year. Jenny is single, and since her income is over $40,000 she will pay 15 percent long-term capital gain. She owes tax of roughly $6885.

If Jenny reports the income, answers yes to the question on virtual currency, and files her FBAR she has no problem at all. Now assume she doesn’t file her FBAR. The highest possible penalty Jenny faces is 50% of the highest value in her account during the taxable year. Just a few days prior to when Jenny sold, the value of her Bitcoin was $56,104.90. So the highest value (so far) of Jenny’s virtual currency account was $336,629.40 ($56,104.90 x 6). Jenny sold one coin for 48,899.90, had a taxable gain of $45,899.90, and owes tax of $6885, but if she is required to report the value of her virtual currency on an FBAR and willfully fails to do so, her FBAR penalty will be $168,314.70, or 50 percent of $336,629.40. If Jenny’s failure is non-willful, she will still have a penalty of $10,000, which exceeds the tax due. Only if she can prove reasonable cause will she avoid a penalty entirely.

In my experience representing taxpayers who needed to disclose foreign finacial accounts or assets to the IRS that were not correctly reported initially, I saw one problem over and over. Taxpayers who don’t know what they need to tell their professional, and tax professionals who don’t know what they need to ask their clients. The importance of working with a professional who knows and understands the rules regarding both FBAR reporting and virtual currency simply can’t be overstated if FinCen does issue amended rules requiring virtual currency to be reported on an FBAR.

*I’m using Bitcoin as an example even though I’m talking about a foreign exchange because the prices are volatile and readily available.