By Chris Farrell, Next Avenue

Increasing numbers of people have found themselves living on low and insecure incomes for decades, including many workers 55 and older. Following the trauma of the pandemic and the social unrest after the murder of George Floyd by a former Minneapolis police officer, addressing the problem of creating a more equitable and inclusive society and economy has taken on added urgency.

“This is foundational,” says Lisa Marsh Ryerson, president of AARP Foundation, the charitable affiliate of AARP. “You can’t tweak around the edges.”

Ryerson is spot on. But where to direct energies and measure improvement (or lack of it) in coming years?

The Problem With Pay and Conditions for Direct-Care Workers

After attending last month’s American Society in Aging (ASA) conference and conducting subsequent interviews, here ‘s my suggestion: Let’s start by improving the pay and employment conditions of the nation’s 4.6 million low-wage, diverse direct-care workers, also known as home care aides and personal nursing assistants.

They’re the ones hired to assist older people who need help with basic tasks such as bathing and getting dressed, as well as other daily chores.

“What we have been wanting is pay equity and social mobility,” says Adrian Haugabrook, the executive vice president at Southern New Hampshire University who participated in the ASA conference session, Equitable Pathways Toward Economic Opportunity. “How do we think about these services and careers?”

Right now, too little.

Direct care is America’s largest occupation and one of the nation’s fastest growing careers. Its workers labor in many settings, including private homes, assisted living communities and skilled nursing facilities. They’re 87% women, 27% immigrants, 59% women of color and 1 in 4 are 55 and older, according to PHI, the leading advocacy and research organization on home health issues.

These are often poverty-level jobs, however. Median hourly wage: $12.80; median annual earnings: $20,300, according to PHI.

“I often get asked why the wages and jobs stayed so low over the decades. It’s a labor force of women, women of color and immigrants that aren’t recognized,” says Robert Espinoza, vice president of policy at PHI and a Next Avenue Influencer in Aging. “They’re invisible in health care and the public imagination. There’s ageism, too. People who are older are also invisible. They [direct care workers] sit at the intersection of all these inequities.”

The Rodney Dangerfield Problem: No Respect

Direct care workers get little respect and status in the broader health care industry. They’re wrongly considered unskilled workers. Turnover rates range between 40% and 60% because many direct care workers tire of making little money, receiving marginal benefits and finding limited career ladders.

“We’ve created a lot of lousy jobs,” says Paul Osterman, an MIT economist and author of “Who Will Care For Us? Long-Term Care and the Long-Term Workforce.”

Yet the demand for home health aides and similar caregiving jobs is on the rise, thanks to the demographics of the U.S. population. There were some 54 million Americans 65 and older in 2019 and by 2030 the U.S. Census Bureau calculates that group will reach 73 million.

The skill and dedication of caregivers I’ve interviewed over the years is striking, too.

Like Susie Rivera of New Braunfels, Texas. She was 63 when we talked last year during the worst of the pandemic and she described caregiving as a “calling,” not a job.

That kind of commitment and dedication is why direct care workers need to be seen as an integral part of any elder’s medical team, Osterman emphasizes in his book.

But attracting workers to the home care industry, and keeping them, requires higher pay, better benefits and, perhaps most importantly, clear avenues for career advancement with training for greater responsibilities.

“It could be done in a way that brings dignity to the patient and their family. A lot of experience would be much more valuable if we reimburse that in a way that took into account the skill of an artisanal dementia coach or home health aide,” said Harvard University economist Lawrence Katz in an interview with PBS several years ago. “That’s the kind of middle-class job that’s going to be extremely valuable going forward as opposed to a ‘McJob’ where a person just does a routine.”

Where will the money come from?

Right now, Medicare typically doesn’t pay for long-term care. Medicaid does, but you generally need to have meager income to qualify for the program. And government reimbursement rates for home care workers are low and inflexible.

Time for a Federal Long-Term Care Program?

Middle-income households typically can’t afford to pay more for direct care workers out of their own pockets. Even today, it’s often a stretch.

The bottom line: Taxes will need to go up to meet the tab. “The only solution is to raise the reimbursement rate and mandate a certain job quality,” says Osterman.

The Biden administration deserves credit for bringing long-term care back on to the national policy agenda. Its American Jobs Plan — better known as the infrastructure plan — proposes hiking federal support for home-based long-term care by $400 billion over eight years. The fact sheet about the infrastructure initiative says the administration wants caregiving jobs to pay more, but is vague on how to accomplish that.

A number of the administration’s training and career advancement initiatives could also benefit direct care workers. So could raising the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour, if Biden succeeds with his policy goal to make that happen.

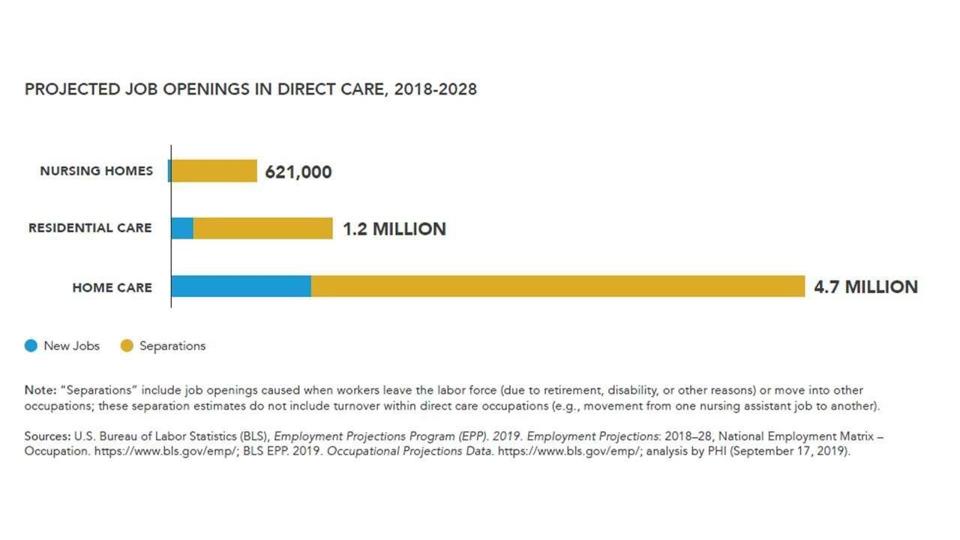

Data: Caring for the Future: PHI, 2020

Even so, direct-care experts say, the country should move away from its reliance on Medicaid for long-term care and the requirement of impoverishment to qualify for it. Instead, Capitol Hill could embrace a long-term care insurance system funded by taxpayers.

“One solution is a public long-term care social insurance program, similar to those operating in nearly every major developed country in the world, except the U.S. and England,” says Howard Gleckman, senior fellow in the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center at the Urban Institute.

Washington state has a three-year-old program that could serve as a model.

It’s funded through residents’ payroll deductions, similar to Social Security and Medicare. The lifetime benefit is $36,500 for those who qualify. This long-term care program is expected to save the state millions in projected Medicaid spending.

Another good starting place is the national blueprint created by the Long-Term Care Financing Collaborative, a bipartisan group of experts.

Seventy percent of Americans surveyed by the Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research said they favor government long-term care coverage through Medicare; 60% support the idea of a government-administered long-term care insurance program.

There are no easy fixes when it comes to overhauling and reforming the nation’s Byzantine long-term care system. But a good starting place is addressing long simmering inequities in the labor market and transforming care work into high-quality jobs for its diverse workforce.

“Shame on us individually and collectively if we do not take the experience and the awareness that has been expanded of the deep divides in the nation,” says Ryerson. “We should rebuild for a better future.”

Quickly, I would add.