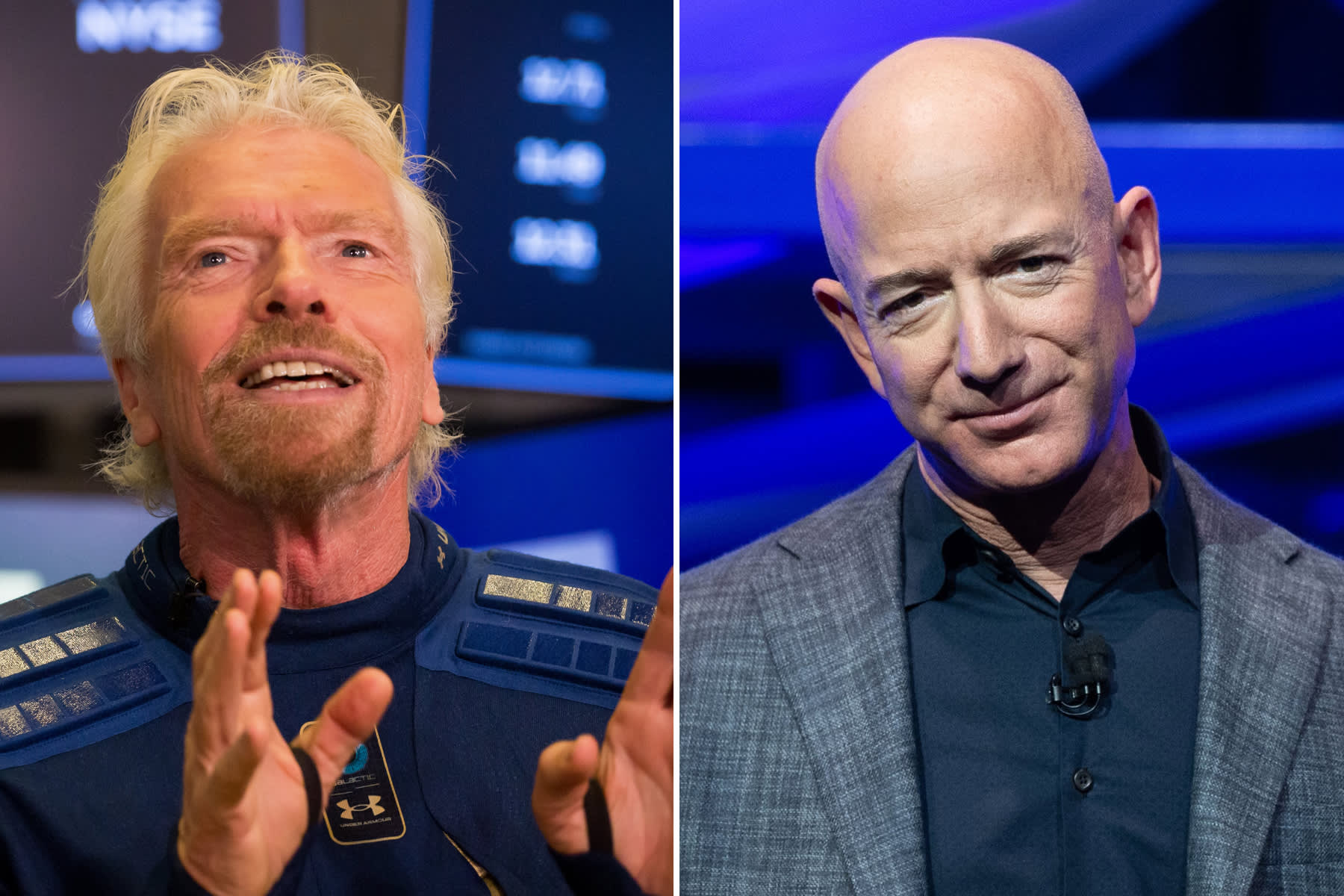

Richard Branson and Jeff Bezos are set to launch themselves just weeks apart, but the exact boundary and experience of their spaceflights has become a point of contention.

Branson’s Virgin Galactic flies above 80 kilometers (or about 262,00 feet), which is the altitude the U.S. recognizes as the boundary of space, while Bezos’ Blue Origin flies above 100 kilometers (or about 328,000 feet), which is commonly known as the Kármán Line.

After Branson said he planned to launch just nine days before Bezos’ previously announced spaceflight, Blue Origin CEO Bob Smith decried Virgin Galactic’s approach as “a very different experience” because “they’re not flying above the Kármán line.”

Virgin Galactic CEO Michael Colglazier responded simply: “We are going above the astronaut line,” adding that it is “the only commercial company that’s flown private astronauts” to date.

On Sunday, Branson plans to launch on Virgin Galactic’s fourth spaceflight test to date. He founded the company 17 years ago, with it now attempting to finish development testing this year so it can begin flying space tourism passengers in early 2022. Bezos’ Blue Origin has goals beyond tourism, but the billionaire is also aiming to fly to the edge of space on the company’s first crewed launch on July 20.

Central to the two billionaires’ dispute is that the line where space begins is not a universally-agreed upon altitude, a fact which astrophysicist Jonathan McDowell emphasized in an interview with CNBC.

“It’s not like the U.S. is one way and everyone else is the other way … there’s no sort of real international agreement,” McDowell said.

There are a variety of reasons McDowell argues that 80 kilometers is the clearest boundary of space, such as the scientific measure of the Earth’s atmosphere, the gravitational physics, and the historical precedent — including that Hungarian-American engineer Theodore von Kármán’s original line was closer to 80 than 100.

McDowell is an astrophysicist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, who published a paper in 2018 with more detail on the debate over the proposed boundary of space. Minor planet (4589) McDowell is named after him.

The spacecraft

Key to understanding the dispute is the differences between the companies’ spacecraft. First and foremost, neither Blue Origin nor Virgin Galactic fly to orbit — both spacecraft are defined as suborbital, capable of carrying passengers to the edge of space to float in microgravity for a few minutes at most. An orbital flight, such as with Elon Musk’s SpaceX, costs tens of millions of dollars and typically spends multiple days or weeks in space.

Blue Origin’s New Shepard rocket launches vertically from the ground, with a capsule for six passengers that disconnects from the rocket booster near the top of the flight. Afterward, the capsule returns to Earth under the control of a set of parachutes, with the booster returning separately to land so it can be launched again.

Virgin Galactic’s SpaceShipTwo system is released mid-air by a carrier aircraft, before firing its rocket engine and arching up in a climb. After performing a slow backflip in microgravity, the spacecraft returns to Earth in a glide for a runway landing.

The difference in the altitude each spacecraft reaches is about 15 kilometers, or 50,000 feet. That difference, McDowell noted, is about “20% higher” and “maybe noticeable” to passengers “but not dramatic.”

“I think experientially, it’s going to be rather similar,” McDowell said. “The important thing is: [The difference] is somewhat arbitrary.”

100 km versus 80 km

In the debate between the altitudes of 100 kilometers or 80 kilometers, McDowell emphasized that “it’s actually not really right to say the rest of the world recognizes 100 kilometers.” He said that aviation records keeper Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI) is “the one official place” that sticks to 100 kilometers, saying again that “it’s not an international law.”

Nevertheless, Blue Origin doubled down on its Kármán line view in a tweet on Friday.

“For 96% of the world’s population, space begins 100 km up,” the company said.

The U.S. recognizes 80 kilometers for a couple of reasons, including space weapons regulations and the historical precedent of early military astronauts. In the 1960s, the Air Force awarded pilots of its rocket-powered X-15 aircraft with astronaut wings after they flew above 80 kilometers.

On the weapons side, McDowell highlighted that “the U.S. has resisted there being any international agreement” on the boundary of space “because they don’t want space to be too clearly defined.”

“Because then it becomes obvious that their missiles go through space and might potentially be subject to space law,” McDowell said. “The general idea is that the U.S. [military] has more freedom of action if it’s not defined.”

On the scientific basis, McDowell gave a physics-based arguments for 80 kilometers, based on the density of the upper atmosphere. Through modeling, his research showed that the edge of the atmosphere “doesn’t wave around that much” and is fairly consistent in its effect on spacecraft.

“If you look at elliptical orbit satellites, you find that they can survive when the closest point of their orbit to the Earth is in the mid-80 kilometers. But whenever it dips to the mid-70s, they just burn up and can’t orbit any more,” McDowell said.

Finally, McDowell says that Theodore von Kármán himself “didn’t originally pick” 100 kilometers as the edge of space. His approach was also “a physics-based idea” and “was somewhere around” the mid-80 kilometer range. But over time, McDowell said people who worked on Kármán’s research decided not to “specify it that accurately” and instead decided “just round it” to 100.

“The Kármán line has become synonymous with 100 kilometers, but that wasn’t originally the definition of the Kármán line,” McDowell said.

Become a smarter investor with CNBC Pro.

Get stock picks, analyst calls, exclusive interviews and access to CNBC TV.

Sign up to start a free trial today.