Danish energy firm Orsted plans to try growing corals on the foundations of offshore wind turbines to find out if the method can be carried out on a larger scale.

In hand with Taiwanese partners, the concept will be trialed in “the tropical waters of Taiwan.” This week’s news represents the latest step forward in the company’s ReCoral initiative, which it started working on back in 2018.

Last year, those involved with ReCoral were able to grow juvenile corals at a quayside site. These were grown on what Orsted said were “underwater steel and concrete substrates.”

The proof-of-concept trials in June 2022 will involve a bid to settle larvae and then grow corals at the Greater Changhua 1 Offshore Wind Farm, a major facility in waters 35 to 60 kilometers (22 to 37 miles) off Taiwan’s coast. The project will use areas measuring 1 meter squared on four foundations.

In a statement Wednesday, Orsted said the goals of the project are to “determine whether corals can be successfully grown on offshore wind turbine foundations and to evaluate the potential positive biodiversity impact of scaling up the initiative.”

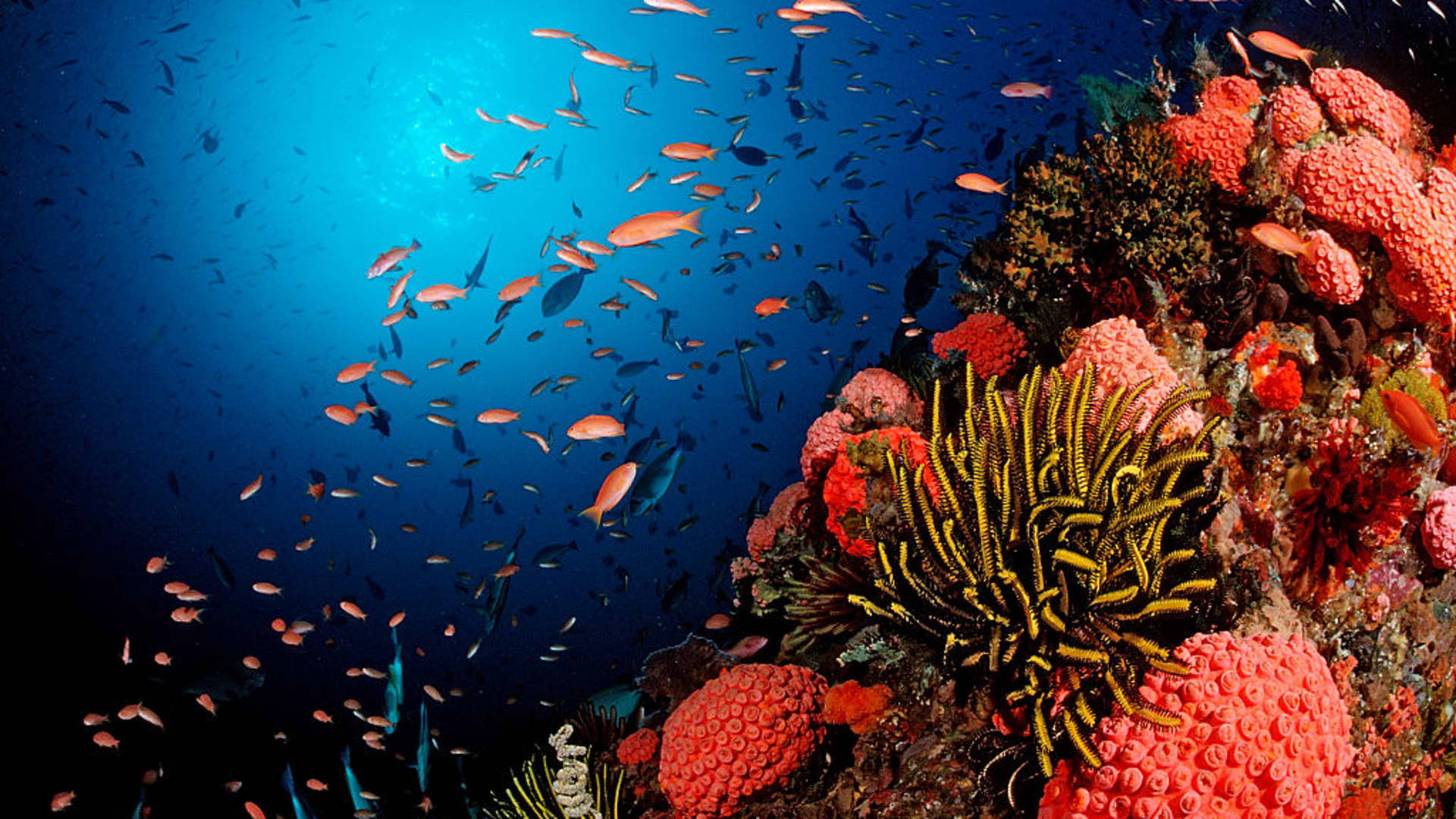

Alongside their vivid beauty, coral reefs have an important role to play in the natural world.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, around one quarter of the ocean’s fish rely on healthy coral reefs. “Fishes and other organisms shelter, find food, reproduce, and rear their young in the many nooks and crannies formed by corals,” the U.S. agency says.

As well as being a source for food and what it calls “new medicines,” NOAA says coral reefs offer protection to coastlines from erosion and storms as well as providing local communities with jobs.

Despite their significance, the planet’s coral reef fast threats including coral bleaching. In March, Australia’s Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, which manages the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park, confirmed a fourth mass bleaching event since 2016.

According to a 2017 factsheet from the GBRMPA, bleaching is what happens when corals are placed under stress, get rid of very small photosynthetic algae — known as zooxanthellae — and start to starve.

“As zooxanthellae leave the corals, the corals become paler and increasingly transparent,” it says.

The authority’s factsheet cites the most common reason for bleaching as being “sustained heat stress, which is occurring more frequently as our climate changes and oceans become warmer.”

While corals can recover from bleaching if conditions change, they can die if things don’t improve.

For its part, Orsted says water temperatures at wind farms located further away from shore can provide more stability, with “extreme temperature increases” prevented by what it describes as “vertical mixing in the water column.”

The overarching idea of the ReCoral project is that this stability in water temperature will restrict the chance of coral bleaching, enabling the healthy growth of corals on turbine foundations.

Whether offshore or onshore, wind turbines’ interaction with the natural world — including marine or bird life — is likely to be an area of major debate and discussion going forward.

In April, the U.S. Department of Justice announced that a firm called ESI Energy Inc had “pled guilty to three counts of violating the MBTA,” or Migratory Bird Treaty Act.

More broadly, the U.S. Energy Information Administration has said that some wind projects and turbines can lead to the deaths of bats and birds.

“These deaths may contribute to declines in the population of species also affected by other human-related impacts,” it says.