Almost have of the banks in the U.S. do not have satisfactory supervisory ratings from the Federal … [+]

On Tuesday, right as most Americans were running around doing last minute preparations for Thanksgiving, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System published the second annual ‘Supervision and Regulation Report.’ I flipped through the first couple of pages which highlight rising loan growth, especially in America’s regional banks, and improved capital and liquidity in the U.S. banking system in comparison to the 2008 financial crisis.

Given the technology, data, and risk management challenges that I see almost on a daily basis at banks, I have to admit that I found the report to be a lot more glowing than I would have expected. It took me until the bottom of page 13 to “Large financial institutions are in sound financial condition, although nonfinancial weaknesses remain.” Nonfinancial refers to pretty important things like data quality, information technology infrastructure, internal controls, model risk management, and governance.

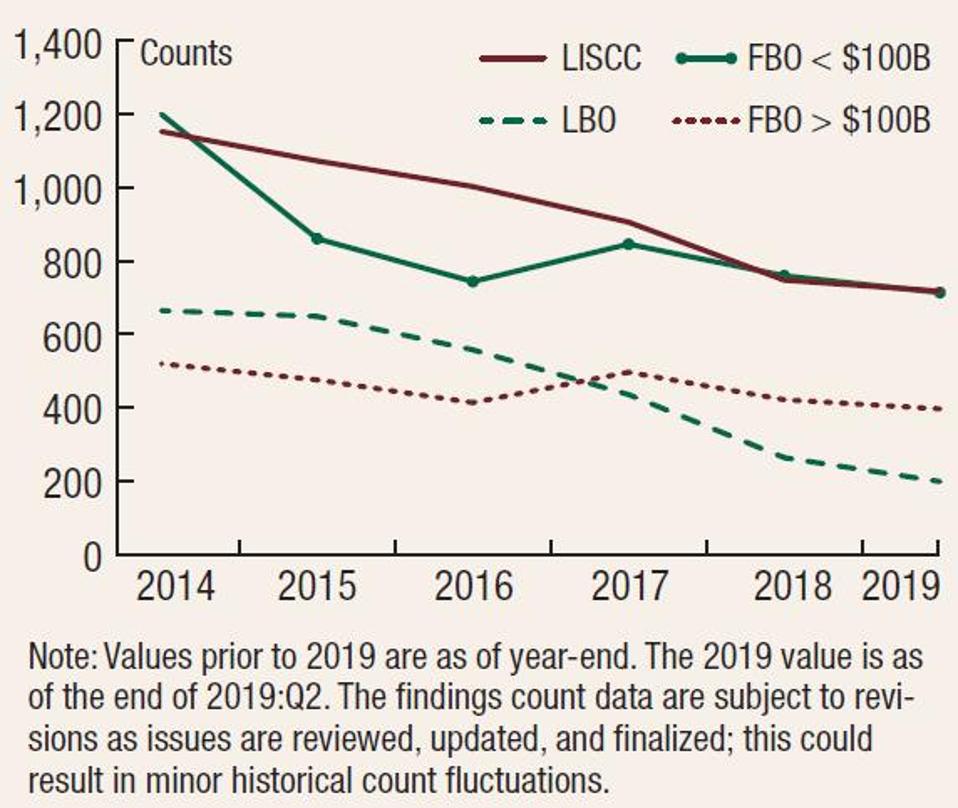

The report’s authors also stated that “Large financial institutions continue to remediate a significant number of supervisory findings (matters requiring attention (MRAs) or matters requiring immediate attention (MRIAs)). As a result, the number of outstanding supervisory findings has decreased over the past year for all groups of domestic and foreign firms.” While it is good that banks continue to remediate matters requiring attention, unfortunately, the report provides no details as to what the outstanding supervisory findings are, what banks have these supervisory problems, and how the challenges were resolved.

Outstanding supervisory findings, large firms and foreign bank organizations

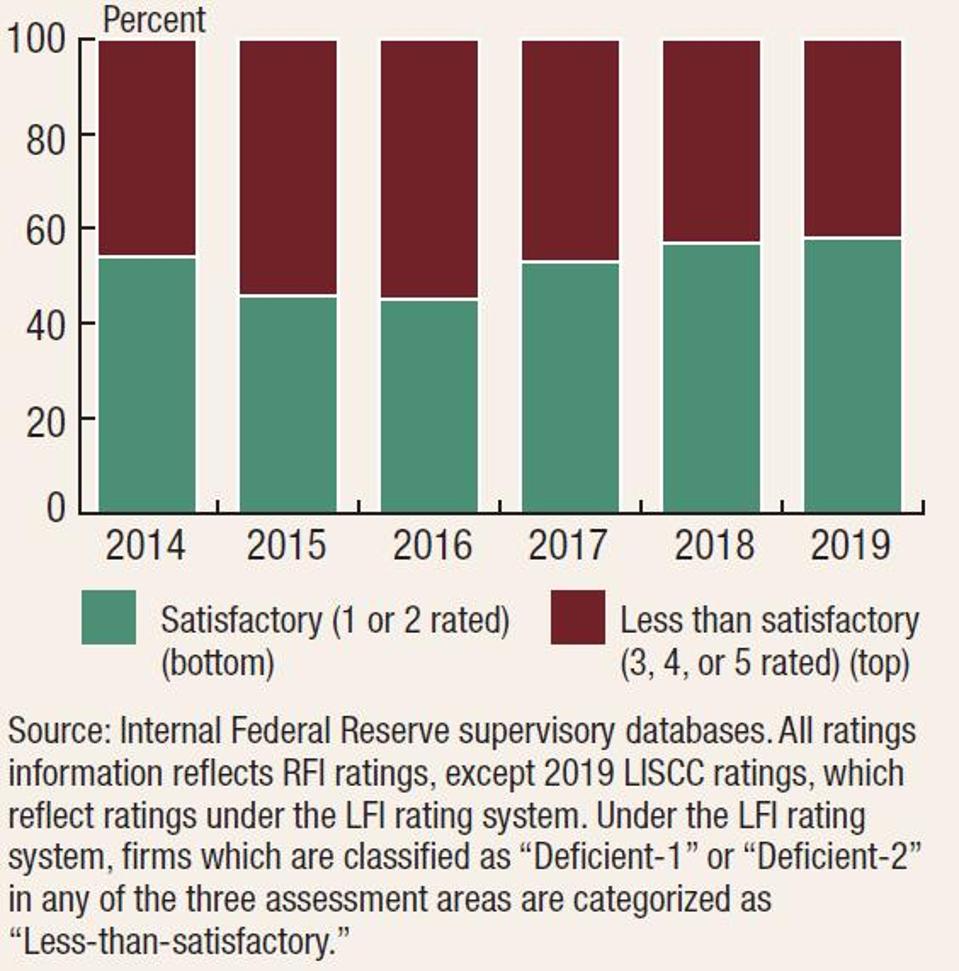

I find it troubling that 45% of U.S. banks with more than $100 billion in assets have supervisory ratings that are less than satisfactory. Satisfactory means getting a ‘C.’ Given that Americans bailed out numerous domestic and foreign banks in the last crisis, we deserve banks that get ‘As.’

The stability of these large banks is important to our country. After the financial crisis, the Federal Reserve developed a supervisory program to address systemic risks posed by large banks. According to the Federal Reserve, “Firms with less-than-satisfactory ratings generally exhibit weaknesses in one or more areas such as compliance, internal controls, model risk management, operational risk management, and/or data and information technology (IT) infrastructure. Some firms also continue to exhibit weaknesses in their Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) and anti-money-laundering (AML) programs.”

Holding company ratings for firms > $100 billion

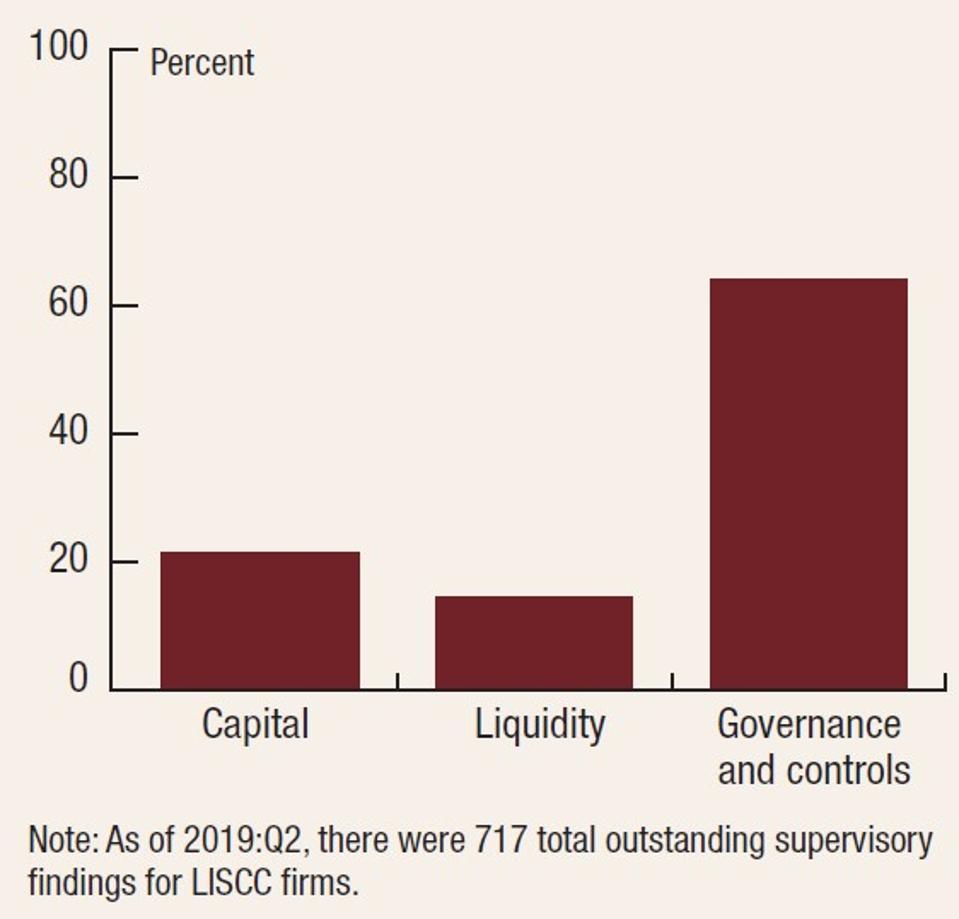

The report explains that over half of the supervisory findings issued in the last five years have been about governance and risk management control issues. Risk management means defining, identifying, measuring, controlling, and monitoring risks uniformly across all of a bank’s legal entities. Currently, sixty percent of outstanding supervisory findings are weaknesses in firms’ Banks Secrecy Act and Anti-Money Laundering programs, internal audit functions, IT risk management (including cybersecurity), and model risk management. Moreover, the Federal Reserve also found that “There are also a number of outstanding supervisory findings related to how firms gather, validate, and report data for regulatory purposes.”

Outstanding supervisory findings by category, LISCC firms

Also of concern should be that over the last year, the percentage of outstanding governance and control issues supervisory findings has increased slightly. The Federal Reserve found that this is consistent with “supervisory concerns regarding weaknesses in these areas and improvements in capital planning and liquidity.” Additionally, Federal Reserve supervisors found that banks are at different stages of improving their technology platforms, data quality, and controls.

The report very briefly also stated that in some American banks, “outstanding supervisory findings relate to firms’ methods for developing assumptions used in internal stress tests and internal governance of capital models, as well as some areas of credit risk management.” If we cannot trust how modelers at banks are developing assumptions for stress tests and if there are problems with governance of capital models, I certainly question the validity of models and take no comfort that banks ‘are passing’ their stress tests. In addition, Federal Reserve supervisors have had to ask some banks to make additional improvements in liquidity risk management in order to meet fully supervisory expectations. “Examples include internal stress tests and cash flow forecasting capabilities.”

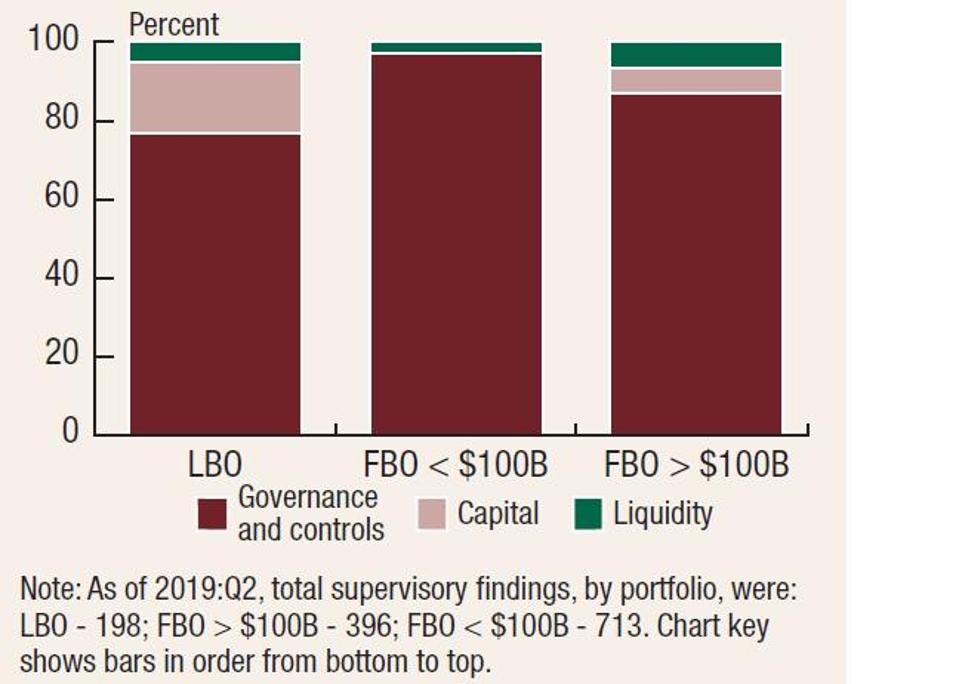

Large foreign bank organizations in the U.S. also continue to have long standing deficiencies with anti-money laundering and IT issues. Findings that the Federal Reserve uncovered in large FBOs over the last year included problems in cybersecurity and information security programs, including patch management, penetration testing, and privacy and also weaknesses in banks’ disaster recovery/business continuity planning.

Outstanding supervisory findings by category, LBO and non-LISCC FBO firms

Given the Federal Reserve’s findings about supervisory challenges, I am concerned about whether we really can trust all the positive information in the first thirteen pages of the report about capital, liquidity, and leverage ratio data. When banks have problems with risk data aggregation and exhibit IT infrastructure weaknesses, we should want more information as to the quality of capital, liquidity, and leverage ratio calculations. Unfortunately, the Federal Reserve report does not tell us which banks have these problems. As taxpayers and investors, we need to be demanding more transparency about our banks, especially as we approach a recession. Moreover, with almost 50% of banks having less than satisfactory supervisory ratings, it is astounding that the Trump administration and bank lobbyists keep pushing for more deregulation. To protect regular Americans, we need more, not less regulation, of any bank not receiving at least a satisfactory supervisory rating.