(Photo by Ben Birchall/PA Images via Getty Images)

PA Images via Getty Images

The Covid-19 pandemic derailed the world’s plans. Weddings, family visits, and business trips have been postponed or cancelled. But of all the derailed plans, the most important are older workers’ retirement plans. Here there are no redos—you only get one shot at retirement. And the recession is making too many take the shot way too early.

For many older workers who took a hit in the pandemic, retirement plans have either receded farther into the future or come rushing up into the present. Workers who were lucky may still delay their retirement plans and work a few extra years. These are largely better-off and more educated white-collar older workers. Other older workers do not have a choice. Due to lost jobs, lost opportunities and lost hope, millions of Boomers are entering an early and involuntary retirement.

More Forced Retirements

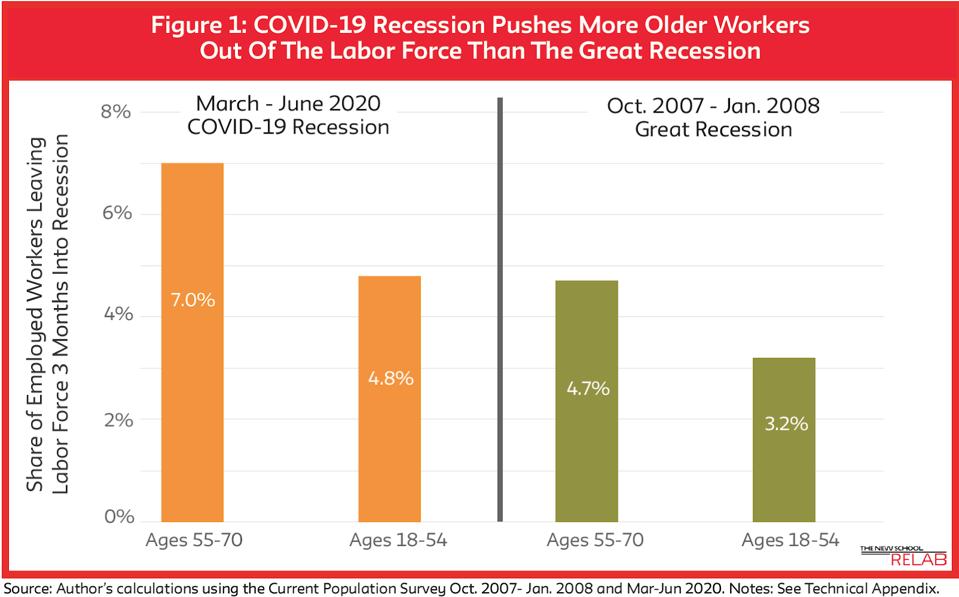

Our most recent research, with coauthors Michael Papadopoulos, Bridget Fisher, and Siavash Radpour, finds nearly 3 million older workers have left the labor force since the pandemic began in March, 2020. This 3 million represents 7% of the workers 55-70 who were working before the shutdowns hit, and who now face the risk of an early retirement. By contrast, only 4.8% of those under 55 who were working pre-Covid in March have left the labor force.

This recession is worse.

Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis

You are out of the labor force when you don’t have job and you are not seeking one. The pandemic recession provides good reasons for people to leave the labor force. Shut down orders make job-finding nearly impossible, especially for workers in hard-hit industries like hotels and entertainment.

But what we are finding a curious phenomenon: labor market participation has failed to pick up as much among older workers as it has for younger workers in the months since unemployment peaked. Of even more concern is the historically high share of older workers who left the labor market since March and now tell government surveyors they are retired. In the early months of the Great Recession (late 2007 and early 2008), 28% of the older workers who had just lost their jobs said they were retired. In the Covid-19 recession, 42% of the newly unemployed older workers say they are retired.

Although these numbers are stunning, and likely unprecedented, involuntary retirement is nothing new. As my team at the Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis found back in 2018, more than half of retiring workers between 2010-2014 left their final job for reasons out of their control. Pause here and take that fact in.

Over half of workers are forced to retire earlier than they wanted.

Some workers are able to or wish they could work longer to bolster their insufficient 401(k) and IRA balances, but many can’t possibly work longer: involuntary retirements is on the rise (the graphic below is from our Retirement Insecurity Chartbook).

Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis

What makes a retirement involuntary?: health and employers who don’t want older workers.

The onset of bad health forces workers to leave their jobs, as does the need to care for family members. Covid-19 is especially dangerous for older people. Many older workers fear ill health if they return to the labor pool.

Older workers still face age discrimination that leads to termination. Whatever the reason for a job separation, unemployed older workers have a far more difficult time finding work than younger job seekers. In the last recession, 2007-2009, the typical older worker searched two to three months longer than younger workers for reemployment. Once re-employed, older workers typically were paid 23% to 47% less than in their previous jobs. Even when older job losers want to keep working, the job market forces retirement on them.

More Forced Retirements to Come

The Covid-19 pandemic threatens to turn what was a steady flow of early exits from the labor force into a tidal wave of involuntary retirements. If the trends over the past five months continue, we estimate that 4 million older workers will leave the labor force by October. That means fewer account contributions in the crucial final years in which workers can save up for retirement. Early retirees will then have to make that smaller asset base last over more years. The ultimate result: downward mobility for middle-class older workers and de facto poverty.

One final point about this cascade of early retirements is that, like so much else in this pandemic, groups that were already marginalized and vulnerable have suffered more than others. Women and nonwhite older workers were more likely to lose their jobs than older white men, and among the job losers, these groups were also more likely to leave the labor force. Among those who lost their jobs, 12% of older nonwhite women left the labor force compared to just 5% of white men. This is just one more way that Covid has exacerbated existing inequalities.

Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis

So much of the damage that Covid has done—worsened by the inaction and ineptitude of the federal government—cannot be undone. But it is not too late for lawmakers to step in and protect older workers from early retirement. The most immediate need is for Congress to extend the enhanced unemployment benefits that expired this week. The weekly $600 payments helped keep the older unemployed from digging into their nest eggs to make ends meet. Not only should these benefits be renewed, Congress should drop the job search mandate for older workers—no one should be forced to seek work at a time when work threatens their lives.

What Congress Should Do To Help Older Workers Forced Out

Beyond the enhanced unemployment benefits, Congress should reinstate the penalty for early 401(k) withdrawals so that older workers aren’t incentivized to raid their retirements in order to scrape by now. And if lawmakers really wanted to help the older workers jolted by the Covid-19 pandemic, they should also consider lowering the Medicare age to 50 and making Medicare first payer in order to lower the cost of employing an older worker.

Just as important as lowering the Medicare age is to expand Social Security to give older workers forced out too early more income. Not only will higher Social Security benefits provide more income to the involuntarily retired, it may give some bargaining power to the reluctant retiree if they ever seek work again. American workers, and thus the economy that depends on retirees’ incomes, were already facing a retirement crisis before the pandemic hit. Now is the time to fully recognize it and take steps to shore up the financial futures of a substantial share of 40 million older workers.