In capital markets, it could be argued that nothing is hotter right now than a special purpose acquisition company (“SPAC”). Whether SPACs are the way of the future or just another fad, they are booming at the moment and the subject of many conversations. Much has been written on SPACs, but little to no ink has been spilled about the income tax and estate tax planning for individual investors. There are both opportunities and challenges for various stakeholders. Here I will lay out a primer on the income and estate tax for the individuals involved on all sides of a SPAC.

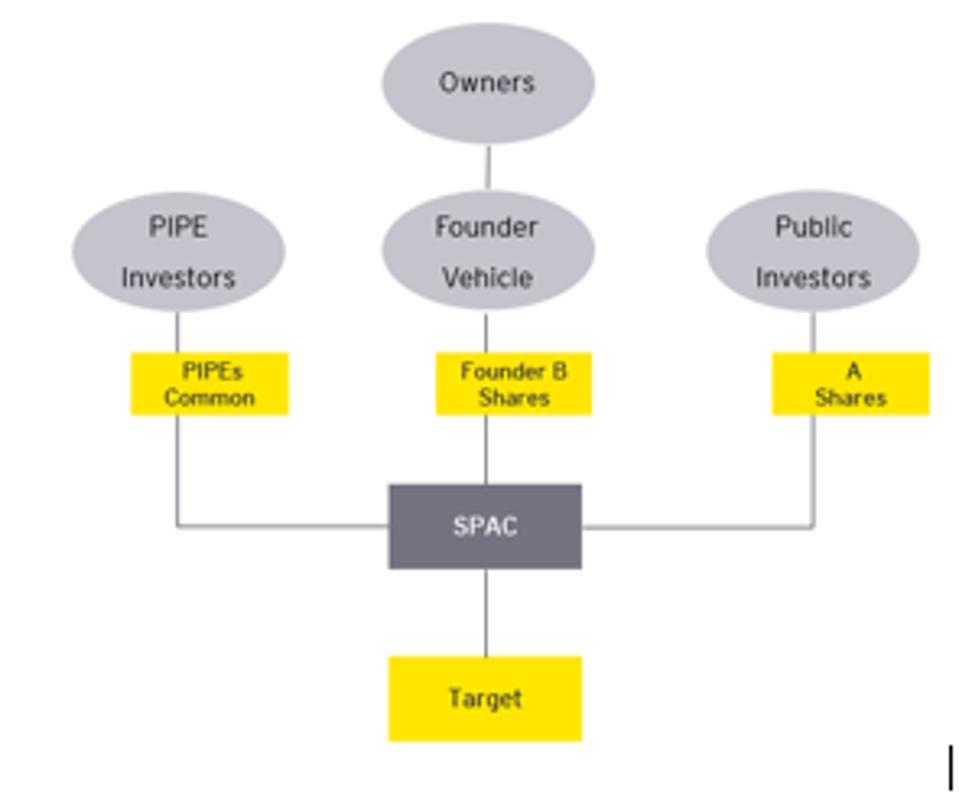

It is too difficult to describe every type of SPAC structure, as the structures vary with the specifics of each deal. The following diagram, however, generally reflects the structure:

SPAC Basic Structure

David Herzig

Now let’s discuss generally how each bucket, the common shares of private investment in public equity (“PIPE”), the Founder B shares, the A shares, and the Target

TGT

are structured and what challenges and opportunities exist for income and estate tax purposes.

SPAC

Income tax issues are associated with the SPAC vehicle. This is mostly because the vehicle itself is often formed in the Cayman Islands, so it is treated as a passive foreign investment company (“PFIC”) and has related issues. For example, since SPACs have only two years to identify a target, they may run afoul of the start-up company exceptions in IRC 1298(b)(2). To deal with PFIC treatment, SPAC investors generally make qualified electing fund (“QEF”) elections. So, SPAC investors face more foreign reporting issues than traditional IPO investors.

Founder B Shares

The sponsor or founder group pays a de minimis amount (usually under a $1 per share) for founder shares equaling 25% (including the 15% green shoe) of the registered shares offered to the public. When the SPAC acquires a target company and completes the de-SPAC process to move the target into the public shell, the founder shares will equal roughly 20% of the value of the SPAC at the time of the IPO. The founder shares are often called the “promote” and come with warrants.

Income tax issues

What income tax questions arise? There is a lot of unpacking here. When the SPAC merges with the target, the founder’s shares convert into identical class A shares. For example, if the SPAC’s IPO is worth $500 million, then the founder shares would be worth $100 million when the de-SPAC acquisition occurs. If the new company goes under after the first month, the public investors and founders would share those losses equally. This differs qualitatively from private equity or hedge fund promotes, which have high-water markets. Those founders have only upside potential.

The income tax issue arise when the founder group receives the promote: is the promote in return for services? This question has generated a lot of controversy. On one hand, the owners are paying for units, which does not sound like compensation. On the other hand, the value of these shares can explode based on the founders’ performance, which sounds like compensation.

To make heads or tails of this, comparisons to traditional structures may be illustrative. In an early-stage start-up, founders often receive compensation in the form of equity. There is a ton of entrepreneurial risk. The entity and the equity basically have no value. Yes, the services performed by the founders might be classified as income, but it would not be realized until the founder disposes of the shares. After all, they could fall to zero at any point until they are monetized.

Say that the company is sold in 2025 after going from $0 to $100 million. A founder receiving 20% of the equity based on work performed would have $20 million in income. This would be taxed at ordinary income rates, currently the top rate of 37% for federal purposes.

However, the tax code provided an option for founders with these types of equity grants. A founder could elect under IRC section 83(b) to take the fair market value of the equity into income in the current year. Using our prior example, the founder would take $0 into income in 2020 because the equity was worthless. When the company is sold in 2025, the $20 million in equity would be taxed at capital gains rates. Because the equity was held longer than a year, the current federal rate of 21% would apply. The 83(b) election would save the founder $5.3 million ([$20,000,000*37%] – [$20,000,000*21%]) in federal income taxes.

But, is this really like a start-up? Or is this like a public issuance with an acquisition? If it is more comparable to the latter, we have a bargain-sale question. For example, the company issues stock to the founders for $1 per share when the stock is worth $10 per share. Is this a bargain sale in which the excess over the $1 is compensation to the founders? But there was no public market for the shares when the founder purchased them and they are restricted, dependent on the consummation of the de-SPAC transaction. This was a blank-check company, so it really is not a bargain sale.

The founder shares seem to follow these two examples. There is a definite business plan to get to a public offering. Without a target and investors, though, the transaction will not consummate; there is entrepreneurial risk. The answer is less than certain; the income tax treatment of the founder shares is an open question.

Estate tax issues

What about the estate tax?

Since the benefit to the founders is a 20% promote with nominal consideration and warrants, wealth-transfer considerations should be taken into account at the SPAC’s launch. For example, assume that the founder’s shares will increase to $20 million from their current fair market value of $25,000. If nothing is done, the entire accretive value would typically be part of the founder’s taxable estate. At the current rates, this could mean that $8 million in estate tax would be due. However, with some common estate tax planning, this estate tax liability could be eliminated.

For example, the founder could place these shares in a 5-year zeroed-out grantor retained annuity trust (“GRAT”). This means that the GRAT would pay back the founder in 5 equal payments of about $5,100 (because the IRS assumes a 0.80% growth factor). This results in a $0.10 gift tax due; the estate tax does not apply to the appreciation over $25,603.1

There are down-sides to GRATs (e.g., mortality risk, and single-generation estate tax mitigation). But the idea is that these assets may present opportunities for estate tax planning, based on a founder’s facts and circumstances.

Conversely, there are challenges. Like other carried-interest planning, IRC 2701 issues exist on the founder side. IRC section 2701 is a special valuation rule that applies to determine the gift-tax value of a transferred equity interest in a privately held investment entity if the transferor or a senior family member holds certain equity interests in the investment entity immediately after the transfer. If the retained equity interests are not properly structured, IRC section 2701 may treat the transferor as having made a deemed gift of the retained equity interests. Since the family or family entities might own the common shares, the IRC section 2701 issues are especially relevant.

PIPE

If additional cash is needed to finance a business combination (e.g., IPO proceeds will not cover the price of the identified target), a SPAC may raise funds in a private issuance of additional equity. Such private issuances often take the form of a “PIPE.” PIPE often lends credibility to the SPAC’s viability and backstops the potential use of trust cash to fund redemptions in the event SPAC shareholders elect to be redeemed in connection with the proxy vote. The more prestigious the PIPE investor, the higher the SPAC’s profile.

PIPE investors often receive the same common class A shares that the public receives, as well as warrants. The income tax questions for PIPE investors tend to be minimal and related to the warrants.

The estate tax opportunities are essentially the same as those for founders with IRC section 2701 concerns.

SPAC Target Company

There are two primary types of targets: (i) easy targets, which are all cash/earnout; and (ii) hard targets, which are some combination of cash and an exchange. Let’s take these one at a time.

For the target getting all cash, there are a couple income tax issues. The first is whether the target was eligible for qualified small business stock (IRC section 1202). There are numerous challenges here; for example, can an S corporation merge with a C corporation, e.g., the SPCA, when the S corporation shareholders perform a tax-free exchange of shares, receiving shares in the surviving C corporation that would be eligible for QSBS treatment? That result seems dubious. But, in a straight purchase in which the target receives cash and qualified for QSBS, could the owners of the target take advantage of the QSBS exemption?

The second income tax issue is the tax receivable agreement (“TRA”) negotiations during the acquisition phase. Under a TRA, the SPAC pays the target shareholders for the value of the corporation’s tax attributes as those tax attributes are used. The most common TRAs relate to (i) incremental tax shield (amortization) resulting from the step-up in tax basis in UpC transactions and (ii) net operating losses, an “NOL TRA.” For example, a target with significant NOLs agrees to pay the historic equity owners over time, generally equal to a portion of the tax benefit of NOLs as they are used by the SPAC to offset taxable income. So, there is a key component of preserving tax attributes in the merger of the target to the SPAC.

Finally, there are other estate tax considerations. Often, the SPAC pays a multiple for the business that exceeds historic fair market value, especially after COVID. For example, assume a company was significantly affected by COVID in 2020. At the end of 2020, the owners did a valuation for the company. It was valued at $100 million. With the SPAC boom, however, the sponsors feel the company is worth $500 million in the SPAC. Can the owners do estate planning?

The short answer is yes, with caveats. It depends on timing. Pre-letter of intent, there should be no constraint on the estate tax approaches. If our owners used a 2-year GRAT on December 31, they would have to be repaid approximately $102 million over 2 years. The exponential growth from the SPAC purchase in 2021 would inure to the owner’s children. This means that, at the end of the 2 years, the original owner would receive back the initial contribution plus an IRS rate of return of $102 million. The other $398 million would transfer to the next-generation beneficiaries of the GRAT with a gift tax due of $0.01. This would save the target’s owner $159.2 million in estate taxes at current rates.1

But, as we approach the letter-of-intent date or pass that date, valuation questions begin to increase. At that point, extensive caselaw, e.g., Ferguson, discusses how valuation becomes fixed once the transaction is certain to close. Since SPACs have a final vote even after the letter of intent by the shareholders, there might be opportunities to do estate planning up to the shareholder de-SPAC vote.

If the target’s owner gets equity in the SPAC as opposed to cash, there are simple income tax questions. As long as IRC section 368 applies in the merger, the target’s owners would receive a carryover basis and tacked holding period on the SPAC shares.

Conclusion

At the end of the day, engaging in a SPAC transaction poses numerous challenges. The implications for the individual owners, however, are too often ignored. Many more issues could be covered here, but this illustrates some of the income and estate tax opportunities and challenges for the various stakeholders.

1 – numbers for illustrative purposes only and should not be relied upon.