As recounted on Twitter and the Illinois politics website Capitol Fax, Chicago’s Mayor Lori Lightfoot had some strong words on pensions at last week’s investor conference:

“We’ve really struggled to get Springfield to pay attention to pensions. . . The problem is not going away, it’s only going to intensify. At some point it’s my hope everyone involved will get serious and come to the table, we know what the solutions are but we lack the political will…it’s not enough if we don’t attack [the] core problem which is a pension system that’s unsustainable in its current state.”

But, when pressed by Rich Miller at that site for specifics of what those known solutions might be, the mayor’s spokesperson had nothing to offer other than a word salad: “pensions are a promise.” We have to “act with a sense of urgency” and “address the City’s pension challenges for the long-term.” “Doing nothing is not an option.” It must be “a collaborative process with labor and legislators.” And so on.

One presumes that Lightfoot’s key (though unspoken) demand is simply for the state to provide more cash for Chicago’s pension funds. The city had previously managed to negotiate its way into state funding of the normal cost, or annual new benefit accrual, for the Chicago Public Schools pensions, because of the disparity between how the CPS and the TRS (the pension for non-Chicago teachers) are financed. But there are no state contributions for municipal workers, or for police or fire employees, anywhere in the state, so there’s no basis for any claim for state funding for the sake of “fairness.”

But is there any other explanation, another way to explain this in a better light?

Lightfoot references the state authorization of a casino in Chicago, which the city hopes will be a source of significant new revenue. Does she hope for new tax revenues of an unspecified nature?

Or is Lightfoot hoping for another try at the “consideration model”? This is the idea that organized labor would agree to pension cuts in exchange for some sort of trade-off, or “consideration.” This is not the same as the ongoing pension buyouts, in which retirees are offered a lump sum in return for giving up their compounded cost-of-living adjustments, and terminated vested participants (those who left before retirement age) are offered a lump sum in return for giving up their pension accruals; these programs, which were started on a one-time basis back in 2018 and made permanent the next year, don’t give actuarially fair cash-outs as required in the private sector but take 30% or 40% off the actuarially-fair value, and, as a result, the number of people choosing the offer has been small.

Instead, the “consideration” model involves a mandatory benefits cut, with a lower-value trade-off in return. The general idea is that participants would be offered a choice of two options, both of which would be benefit cuts compared to the present benefit formulas; either pensionable salary would be frozen or COLA benefit provisions would be reduced. This was championed by then-Senate President John Cullerton in 2013, but lost out to the final version of reform which the Illinois Supreme Court deemed unconstitutional; however, politicians continued to propose it in 2017 and in 2019 and House Republican Leader Jim Durkin recently suggested it could still be on the table. In any case, I am among the skeptics who find it hard to believe that simply offering a choice of benefit cut options would make benefit cuts more acceptable to the Court.

Or, lastly, does Lightfoot have in mind a fundamental change in the city’s pensions for new hires? This is more complicated.

It is true that the situation is not as dramatic as for the new-hire non-Chicago teachers, who subsidize the rest of the system with their 8% contributions, but the Tier 2 and Tier 3 benefits did make substantial cuts for newly-hired employees beginning in 2011, increasing the retirement age and imposing pay caps, COLA changes, and other changes. For the Municipal Employees, which comprises almost half the city’s total pension liability, this had the effect of essentially removing the city’s retirement contribution entirely, if we remove the element of risk. For the Police and Fire, the early retirement ages are a key driver of their benefit costs, and even the Tier 2 benefit changes did not alter this much; in addition, the annual benefit accrual factor is higher to account for the fewer number of years worked — but one doubts that Lightfoot’s reference to “political will” refers to a desire to increase the retirement age for police and fire retirees. In any case, there’s not much low-hanging fruit to be found here, in the form of cost reduction. (Scroll down for a few tables as a sort of footnote.)

Of course, none of this should be a surprise. Lightfoot has repeatedly called for “action” with respect to pensions without providing any specific plan.

The only real paths forward that I see are these:

First, a complete re-do of the retirement benefits for newly-hired employees into a hybrid system completely unlike the current system. This means, yes, beginning to participate in Social Security, like almost everyone else, and adopting a risk-sharing system for supplemental retirement benefits, similar to, yes, the fully-funded Wisconsin system. City workers would not be left to share all risks by themselves, as with a 401(k) plan, but risks would be pooled, so no one need worry about outliving their assets. However, like a 401(k) plan, the city would have a fixed contribution, and would be forced to make that contribution, with no greater ability to take a “contribution holiday” than they would have, to simply decide not to cut paychecks if the budget was tight.

This would not in itself reduce costs. But if, and only if, the system has been wholly changed, it would become much easier to consider the past liabilities as legacy costs, in the same manner as other city debt.

Second, a constitutional amendment giving the state the ability to change future accruals for existing workers is stymied by the same lack of trust that caused the graduated tax amendment to fail. But what if an amendment were proposed which made it clear, in the amendment’s text itself, that no changes would be made except to retirees with particularly high pensions or workers with particularly high salaries, so that voters could be assured that financially-struggling workers and retirees would be unaffected: “Membership in any pension or retirement system of the State, any unit of local government or school district, or any agency or instrumentality thereof, shall be an enforceable contractual relationship, the benefits of which shall not be diminished or impaired, for any plan participant whose salary or retirement benefit is less than the median salary or retirement benefit, respectively, in the state of Illinois.” Or, heck, “less than the 75th percentile”, or some similar threshold, that makes it clear that most workers remain protected.

This, not a state bailout or some unanticipated new revenue, would be a real path forward.

As always, you’re invited to comment at JaneTheActuary.com!

Footnote:

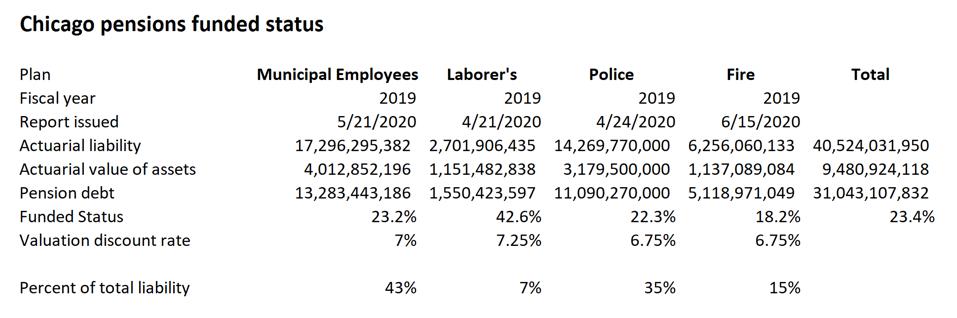

Here are two key charts summarizing Chicago’s pensions as of their last valuation date, at the end of 2019, that is, without any covid impacts on the liabilities or assets, first the key funded status figures,

Key data, city of Chicago pensions

own work

and, second, the normal cost and employee contributions for each plan.

Normal cost, Chicago pension plans

own work

Actuaries may wish to know that these calculations are based on the Entry Age Normal funding method used by all four of the plans. The reports from which these values are taken can be found at these links: Municipal, Laborers’, Police, and Fire.