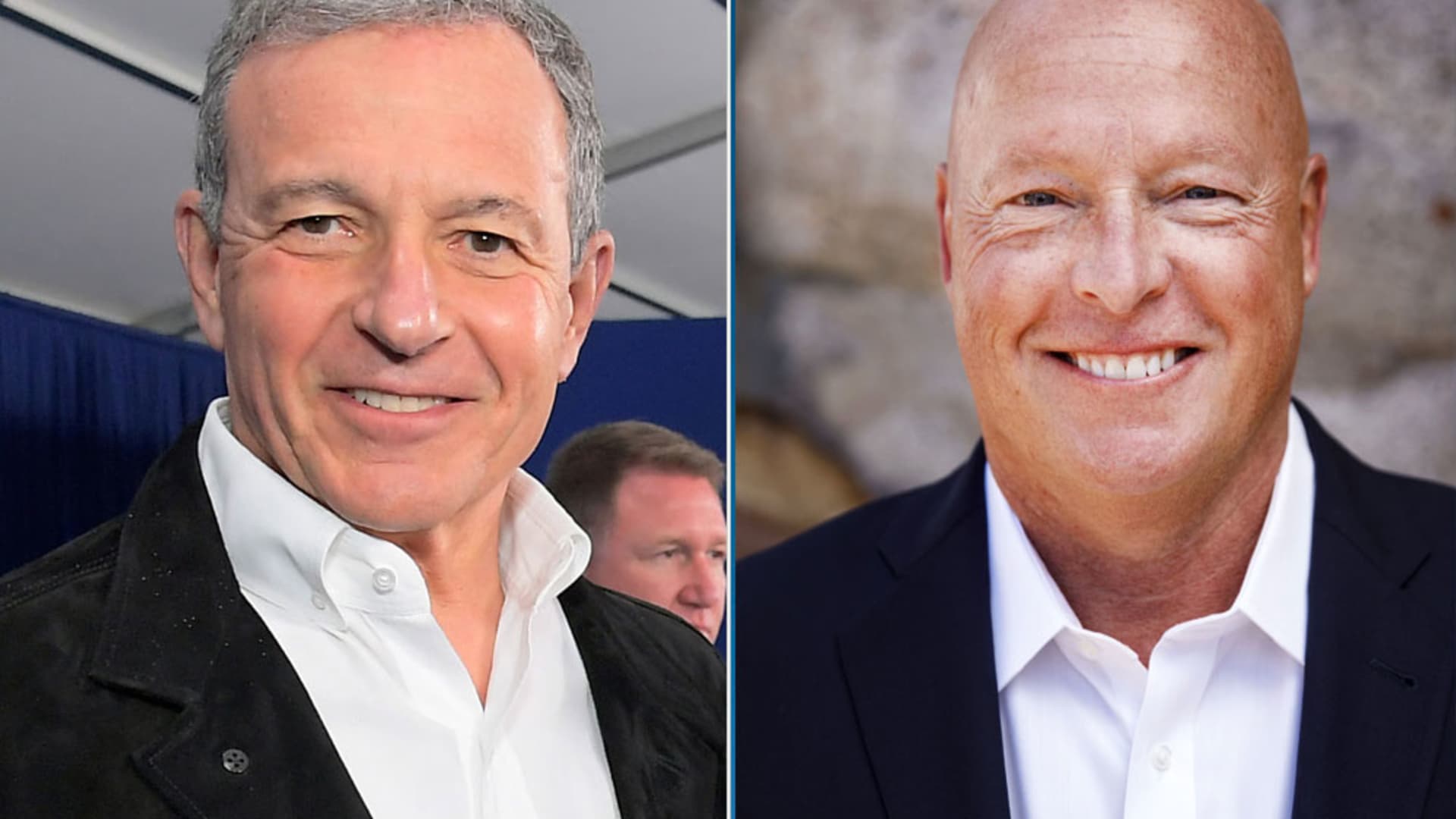

April 12, 2020. That’s the day former Disney CEO Bob Iger’s relationship with his handpicked successor, current Disney CEO Bob Chapek, began to fall apart.

Iger had stunned the world in February of that year by resigning as Disney’s chief executive, effective immediately. He elevated Chapek, whom Iger and the board had long seen internally as the front-runner for the position given his operational experience and decades at the company. Iger would stick around as executive chairman and direct the company’s “creative endeavors” to help with the transition.

The timing of a CEO change at arguably the world’s most famous entertainment company couldn’t have been worse. Just weeks after Iger stepped down, Disney began closing its theme parks around the world during the initial stages of the Covid-19 quarantine.

Iger and Chapek seemed to be ready for the pandemic challenge together.

“I can’t think of a better person to succeed me in this role,” Iger said March 11, 2020, during the company’s annual shareholder meeting, a day before the company closed its parks.

Chapek returned the optimism.

“I’ve watched Bob [Iger] lead this company to amazing new heights, and I’ve learned an enormous amount from that experience,” Chapek said.

One month after those comments, with everyone stuck at home, then-New York Times media columnist Ben Smith published a story after reaching Iger by email. He reported Iger wasn’t going to turn Chapek to the wolves as a brand-new CEO while the world was falling apart. Iger told Smith he would stick around to help run the company.

“A crisis of this magnitude, and its impact on Disney, would necessarily result in my actively helping Bob [Chapek] and the company contend with it, particularly since I ran the company for 15 years!” Iger said in his email.

Chapek was furious when he saw the story, according to three people familiar with the matter. He had not expressed a need or desire for extra help. He wasn’t looking for a white knight. Iger had postponed his retirement as CEO three times already. Chapek felt he was essentially doing it again, leaving him as a hapless second banana, according to people familiar with his thoughts. Chapek was already reporting to Iger, the board’s chairman, anyway.

The Disney board had little interest in starting a brawl, especially given the state of the company and the world, the people said. Three days after Smith’s story was published, Disney accelerated its timeline and named Chapek to its board.

“It was a turning-point moment,” said one of the people familiar with Chapek’s reaction to Iger’s interview with Smith.

Since that incident, Iger and Chapek haven’t been able to mend their relationship, according to about a dozen people familiar with the matter who spoke with CNBC for this story. The people asked to remain anonymous because the relationship and discussions about it are private.

In the months that followed, Chapek began making key decisions about Disney’s future — including a dramatic reorganization of the company and outing actress Scarlett Johansson’s salary following a dispute over her Marvel movie “Black Widow” — without Iger’s input. Internal messages about business strategy from both men would sometimes conflict, as it became clear the executives weren’t speaking with one voice, several people noted.

While much of the public narrative has centered around Iger’s “long goodbye” — he departed as chairman in January — Chapek, 61, has actually been firmly in control of Disney for more than 18 months.

Normal times would have allowed Iger and Chapek to work more closely. Instead, the two executives barely spoke to each other. Chapek has a small circle of close confidants with whom he makes major decisions — longtime right-hand man Kareem Daniel, chief of staff Arthur Bochner, and, to some degree, Chief Financial Officer Christine McCarthy, whom Iger promoted to the role in 2015, according to people familiar with the matter.

Iger hasn’t been part of that circle.

In December, just days before his departure as executive chairman, Iger threw himself a going-away party, inviting more than 50 people at his house in Brentwood, a suburban Los Angeles neighborhood. He spoke at length about his time at Disney in front of the crowd. Chapek attended, but there was little interaction between the two men, according to people who attended the party. Guests — including veteran Disney executives and on-camera talent, such as broadcasters Robin Roberts, David Muir and Al Michaels — sat at two long tables at Iger’s house.

Iger and Chapek sat at opposite tables. Chapek sat near several of his direct reports, including Daniel. Iger sat next to film director and mogul Steven Spielberg. While Iger spent about 10 minutes publicly praising former colleagues, he barely mentioned Chapek, said the people.

“It was extremely awkward,” said one of the guests, who asked to remain anonymous because the party was private. “The tension was palpable.”

Both Iger and Chapek declined to comment on their relationship with each other.

Iger’s shadow

Chapek’s decision to move away from Iger showed chutzpah, but it also put him on an island against a Disney icon, who also happened to be the chairman of his company and a large shareholder. He also hasn’t been able to benefit from the myriad relationships Iger developed from decades at Disney.

Anyone succeeding Iger, who had been Disney’s CEO since 2005, was going to have a difficult time filling his shoes. Iger was generally beloved by Hollywood and highly respected as a CEO, particularly after orchestrating a series of intellectual property acquisitions — of Pixar, Marvel and Lucasfilm — which will likely go down in media history as three of the smartest deals ever. Iger, 71, has even flirted with running for president of the United States.

Chapek, meanwhile, has a harder exterior and at times, according to colleagues, struggles with emotional intelligence — which happens to be Iger’s strength.

The differences between the executives’ leadership styles have come to light quickly in Chapek’s tenure.

Disney’s public spat last year with Johansson over compensation after “Black Widow” streamed on Disney+ at the same time it hit theaters during the pandemic embarrassed Iger, who prided himself on smooth relationships with A-list talent. While the controversy happened under Chapek’s watch as CEO, Iger was still chairman and working with creative talent.

This month, Chapek’s public acknowledgement that he let Disney employees down by not fighting harder against Florida’s “Don’t Say Gay” legislation has been another reminder to Iger loyalists that Disney’s brand may be at risk with Chapek at the helm. Weeks before, Iger took a public stance against the legislation.

The messy execution has angered Disney employees. Deadline reported it spoke with several longtime Disney employees who said Chapek’s handling of the situation led to “the worst week they’ve ever had working at the company.” Several Disney employees have called Iger in recent weeks to express their disappointment in Chapek, according to two people familiar with the matter. Chapek met with creative leaders at Disney earlier this month to hear their concerns about his response to the bill, CNBC previously reported.

Perhaps the biggest division between Chapek and Iger was a more mundane one — Chapek’s decision to remove so-called profit-and-loss, or P&L, power from many of Disney’s veteran division leaders and consolidate all of that control under Daniel.

While public controversies generate headlines, it’s likely to be Chapek’s internal changes, and how successful they become, that will determine his future as Disney’s CEO.

Centralizing Disney leadership

In October 2020, about eight months after he took over as CEO, Chapek announced Disney was strategically reorganizing its media and entertainment businesses. This was Disney’s second major reorganization in less than three years. The key part of the announcement was the following:

“The new Media and Entertainment Distribution group will be responsible for all monetization of content —both distribution and ad sales — and will oversee operations of the Company’s streaming services. It will also have sole P&L accountability for Disney’s media and entertainment businesses.”

Those two sentences upended how Disney has done business for decades. The change gave Daniel, the leader of the new Media and Entertainment Distribution group, called DMED internally, one of the most important jobs in the history of media. The decision was instantly polarizing, leading to a burst of internal frustration among some veteran Disney employees who no longer controlled the budgets of their divisions, according to people familiar with the matter.

Chapek wants to streamline Disney so content decisions across distribution platforms can be made in synchrony. Instead of division heads running their own fiefdoms, Chapek and Daniel can steer Disney by controlling the budgets of each group and deciding where content ends up — streaming or cable or broadcast or movie theaters. Executives can then focus on making content, or selling ads, or building streaming technology, with direction from Chapek and Daniel. Historically, the heads of Disney TV or ESPN or Hulu or film would run their entire businesses.

Conceptually, Chapek’s idea actually isn’t all that different from what Iger had begun to put in place with the organization of Disney+. In early 2018, Iger met with Robert Kyncl, chief business officer at Google’s YouTube, according to people familiar with the meeting. Before Google, Kyncl had worked for seven years at Netflix, overseeing content partnerships.

Kyncl told Iger if he wanted Disney to start trading at Netflix-like multiples — which were, at the time, orders of magnitude higher than Disney’s — Iger needed to run operations like a technology company. Google separated its content and distribution divisions. The same roles didn’t live within smaller groups, the way Disney had been structured for years.

Kyncl declined to comment to CNBC about the meeting.

If Disney wanted investors to see its burgeoning streaming service as the growth engine in a digital-first world, Iger realized he needed to centralize power around Disney+. According to two people familiar with the meeting, Iger urgently asked then-Disney head of strategy Kevin Mayer to return from the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas so Iger could show him a new organizational structure, which he drew on a whiteboard in front of Mayer. Mayer would become the head of Disney’s new direct-to-consumer unit, in charge of the company’s streaming platforms: Disney+, Hulu and ESPN+. Disney officially reorganized in March 2018.

Power struggles followed. Mayer and Disney TV studio head Peter Rice fought about who had the authority to decide which shows aired on Disney+. Rice’s principal issue was that content executives could no longer have direct conversations with Hollywood talent and tell them whether Disney would make their show or not. Rice feared losing greenlight power would affect Disney’s relationship with Hollywood. If studio executives didn’t have the power to approve projects, they’d quickly lose credibility with creators, who would want to speak with the people at Disney who possessed that authority.

Iger had to solve the disputes by making control decisions on the fly. Mayer won the main argument — he would have greenlight power for Disney+. Mayer left Disney in 2020 to become TikTok’s CEO, months after Iger chose Chapek as CEO.

Mayer and Rice declined to comment for this story.

While Chapek didn’t consult Iger about his October 2020 reorganization, he did cite many of the same principles that Kyncl and Iger discussed in 2018.

“Managing content creation distinct from distribution will allow us to be more effective and nimble in making the content consumers want most, delivered in the way they prefer to consume it,” Chapek said in a statement announcing the changes.

When he became CEO, Chapek went on a listening tour of executives to find out what was working and what wasn’t. He heard from both distribution and content executives that the current arrangement had become dysfunctional.

Chapek decided to reverse Iger’s decision to have greenlighting authority rest with the head of the streaming services. He gave that power back to content heads, who have more money than ever before to make programming — Disney plans to spend a record $33 billion on content for fiscal 2022. That’s largely pleased Disney’s content leaders, who can now tell creators directly whether Disney will work with them, according to people familiar with the matter.

But with Daniel getting P&L control, long-term Disney executives also lost the ability to run the businesses of their own divisions. Some creative leaders didn’t mind, preferring to focus on making content rather than selling advertising or working on wholesale distribution agreements with pay-TV providers. Others didn’t appreciate their loss of control over budgets.

Kelly Campbell’s decision to leave her job running Hulu to lead NBCUniversal’s Peacock in October was at least partially motivated by her desire to have more control over a business than what Disney allowed her, according to a person familiar with her thinking.

Campbell declined to comment for this story.

One film executive told CNBC that Disney operated smoothly when Alan Bergman, chairman of Disney Studios, and Alan Horn, former chief creative officer of Disney Studios, were in charge of the studio’s P&L. Film producers knew standard facts, such as a movie’s marketing budget or a film’s release date. In the new world, with Daniel in charge, it’s much harder to find out answers because the creative point people simply don’t know, the person said.

Others saw Chapek’s restructuring as simply pushing the envelope on a trend Iger already started —making it clear to Wall Street that streaming was the company’s new priority. By putting Daniel in charge of a variety of different budgets, Chapek could more easily steer all of Disney in the same direction. Decisions could be made more quickly.

This month, Disney put its new Pixar movie “Turning Red” directly on Disney+ instead of in theaters first. That decision would have taken “months” under Iger’s structure, with division heads flexing their power and knowledge of the market, according to three people who participated in the discussions. Instead, the debate took weeks, with Pixar executives ultimately agreeing that the movie should go to Disney+ first, the people said. “Turning Red” is the No. 1 film premiere on Disney+ globally to date, based on number of hours watched in the first three days.

As with any corporate reorganization, the proof will be in the results. Disney has a target of 230 million to 260 million global Disney+ subscribers by the end of 2024, compared with about 130 million Disney+ subscribers today. If Disney can get there, Chapek and Daniel can claim success — assuming they also revive the company’s shares, which have fallen about 30% in the past 52 weeks, even as crowds have returned to Disney’s theme parks around the world.

Kareem Daniel

Daniel’s P&L oversight for all movie, TV and film distribution, advertising, sales, technology and other divisions — jobs that used to be done by a cadre of Disney employees with 20 or 30 years experience each — gives him one of the most powerful jobs ever created in media. Disney’s fiscal 2021 revenue topped $67 billion and has a market capitalization of about $240 billion. Disney routinely outspends all other global companies by billions of dollars a year on entertainment content.

Iger never agreed with giving Daniel so much control. The former CEO felt stripping division heads of their budget control wasn’t the right structure for Disney because the company was too diverse and complex.

Daniel is a polarizing figure among colleagues who have worked with him.

He’s described by five former and current co-workers as smart, hard-working and gregarious. He studied electrical engineering and got an MBA from Stanford. He’ll slap people’s backs and is fun to engage with outside of work, three of the people said. He’s demanding of his direct reports and holds them accountable, the people said.

Daniel is Black, an extreme rarity among the primary leaders of global media companies. He’s the first Black senior executive ever to report directly to the Disney CEO in the history of the company. That carries weight with certain employees, who respect the symbolism of a minority leader in such a high-profile role.

Like Chapek, Daniel has worked in a variety of Disney units, including studio distribution, consumer products, games and publishing, Walt Disney Imagineering, and corporate strategy. He’s been close to Chapek for two decades, first working for him as an MBA intern in 2002. When Daniel moved to corporate strategy, he again worked with Chapek on a variety of projects in 2007 and 2008. He worked under Chapek in distribution for Walt Disney Studios in 2009, when he was part of the M&A team that bought Marvel Entertainment, before following him to consumer products in 2011.

Chapek was particularly impressed with Daniel’s consumer focus when the two worked together to shorten the theatrical window from four months to three months at the end of 2009, according to a person familiar with the matter.

But some of the same people who note Daniel’s strengths also told CNBC the job may be too big for him — or almost anyone.

“He arguably has the most important job at Walt Disney, outside of CEO, and he has almost no experience running any of these businesses that were previously run by people that had decades of experience,” said one former coworker.

Chapek disagrees with that assessment, according to a person familiar with his thinking. He understands the job is massive in scope but feels that Daniel is suited to handle it given his varied experiences at Disney, including as president of consumer products, games and publishing, and president of operations at Walt Disney Imagineering.

Since his promotion announcement in October 2020, Daniel hasn’t done any published or televised interviews. He declined to comment for this story.

‘One Disney’

Ideally, Chapek would like consumers to experience a more unified digital Disney experience, whether it’s logging into Disney+ or buying merchandise from the online Disney store or managing theme park experiences with Disney’s Genie service, which is a kind of digital concierge. Internally, some employees informally speak of this grand challenge of unifying Disney technology and experiences as “One Disney.”

Chapek and Daniel want to hasten the pace of Disney’s digital transformation. In January, Chapek established company goals to “set the stage for our second century, and ensure Disney’s next 100 years are as successful as our first.” Two of the main themes were breaking down silos and innovation.

Disney, by nature and history, isn’t a technology company, even though it’s trying to restructure itself to be like one. In general, its employees don’t have the same type of technological know-how that you’d find at Apple and Google.

That’s problematic for a company that wants to trade at a technology-like multiple. According to a person familiar with the matter, Disney has struggled to build back-end technology to sell advertising on all of its streaming services — Hulu, Disney+ and ESPN+ — and traditional distribution channels. Disney+ and ESPN+ run on streaming infrastructure from BAMTech, a spin-off of MLB Advanced Media that Disney bought in 2017. Hulu has its own separate infrastructure.

Chapek and Daniel are still trying to streamline the organizational structure. Disney hires people dedicated to marketing or selling ads for its streaming services, ESPN, ABC and Disney’s entertainment cable networks, including some from its acquisition of 21st Century Fox. Those jobs can be duplicative and work against a “One Disney” experience.

Chapek has several times mentioned Disney building its own metaverse, although he hasn’t gone into detail about what exactly that means. Last month, Chapek promoted veteran executive Mike White to be Disney’s senior vice president in charge of “next generation storytelling.” In a memo seen by CNBC last month, Chapek said White’s goal will be “connecting the physical and digital worlds” around Disney entertainment.

Chapek will also have to decide what to do with Disney’s current assets. Some media analysts, such as LightShed’s Rich Greenfield, have argued Disney would be best off spinning out ESPN and combining it with a digital sportsbook. But that hasn’t been Chapek’s priority. ESPN relies on traditional TV affiliate fees, and it may not be strategically aligned with Disney’s direct-to-consumer ambitions, but the company has no plans to spin off or sell the sports network, said people familiar with the matter. ESPN has considered licensing its name to sports betting companies, but Disney isn’t interested in buying one, the people said.

Chapek will need time to show his own employees and shareholders that he can be trusted to accomplish goals he lays out. Nearly everyone interviewed for this story said that while Chapek may not be a “people person,” he’s a skilled and determined operator. Disney’s fiscal first-quarter results blew away analyst estimates on earnings per share, revenue and total Disney+ subscribers.

Several current Disney executives noted that Chapek’s No. 1 priority — setting up Disney for a digital world where streaming dominates and legacy distribution models fade away — is exactly what Iger believed in. That adds an element of sorrow to the men’s failed relationship. Their end goals are the same.

It’s possible Disney employees and the broader media and entertainment world simply get used to Chapek’s method of leadership with time. Chapek clearly isn’t Iger, but perhaps his biggest challenge will be convincing everyone it’s OK not to be.

Chapek’s contract is up at the end of February 2023.

Iger regrets how the change of control has transpired, one person said. But he’s also not returning to Disney, he told Kara Swisher in a January interview.

“I was CEO for a long time,” Iger said. “You can’t go home again. I’m gone.”

Disclosure: NBCUniversal is the parent company of CNBC.

WATCH: Disney CEO Bob Chapek addresses Florida’s ‘Don’t Say Gay’ bill