You think you’re going to earn a lot investing a lump sum? You’re thinking wrong.

Future value

I’ll grab the money now and invest it, you tell yourself. Get Social Security early, or take the lump-sum buyout of a corporate pension. I can put the cash in the stock market and earn way more than I’d be getting by waiting for the money.

Do you think like this? If you do, you have lots of company, including some very smart people. You, and they, are thinking about this wrong. You’re throwing away thousands of dollars.

The mistake is easy to make. That corporate pension may have, built into it, a 4% annual return. You figure you can 6% or 8% on stocks. So it seems to make sense to get the cash now and invest it.

The fallacy here is confusing a stock with a bond. The pension is a bond (or more precisely, a collection of bonds). By cashing out and investing, you sell a bond and buy a stock. This is not a smart move if you sell the bond at a crummy price.

Most of the people taking corporate lump sums, or claiming Social Security before age 70, are selling bonds at crummy prices. They’re getting 70 to 90 cents on the dollar. This is foolish. If you really want to buy more stocks, find some other way to finance them. Look around for bonds you can sell at full market value.

Review your 401(k). Is it already fully invested in stocks? Probably not. If it’s in a target date fund, it has a bond allocation, and if you’re close to retirement that allocation is going to be high. You can shift from stocks to bonds by shrinking the target fund and using the proceeds to buy a pure stock fund. When you do that, you are selling bonds at 100 cents on the dollar.

What about that 529 college account for your 15-year-old? The account is probably heavily in bonds. Switch it to pure stocks if you want to boost your family’s exposure to the stock market.

It doesn’t matter that college is around the corner and the kid doesn’t want to take chances. When you change the portfolio to stocks, promise your youngster to make up the loss if the market crashes. Using the college fund enables you to take money out of bonds at a good price and invest in stocks.

I’m not saying that a 100% stock market allocation is wise, either for someone about to retire or for a family with college costs looming. I’m just saying that if you want to have more stocks, it’s a bad idea to get them by selling bonds for less than the bonds are worth.

Couples claiming Social Security early are in some cases throwing away $100,000 or $200,000. Many of the General Electric pensioners cashing out for lump sums are getting not much more than half of what their annuities are worth.

Before cashing in an annuity (or turning down the enhanced Social Security benefit granted to those who wait), calculate the value of the bonds you are in effect selling. In this calculation, the discount rate is the yield on bonds; what you expect from stocks is irrelevant.

This is a complicated calculation, involving as it does mortality tables, your health and the yield curve in the bond market. But I’ve done the work for you.

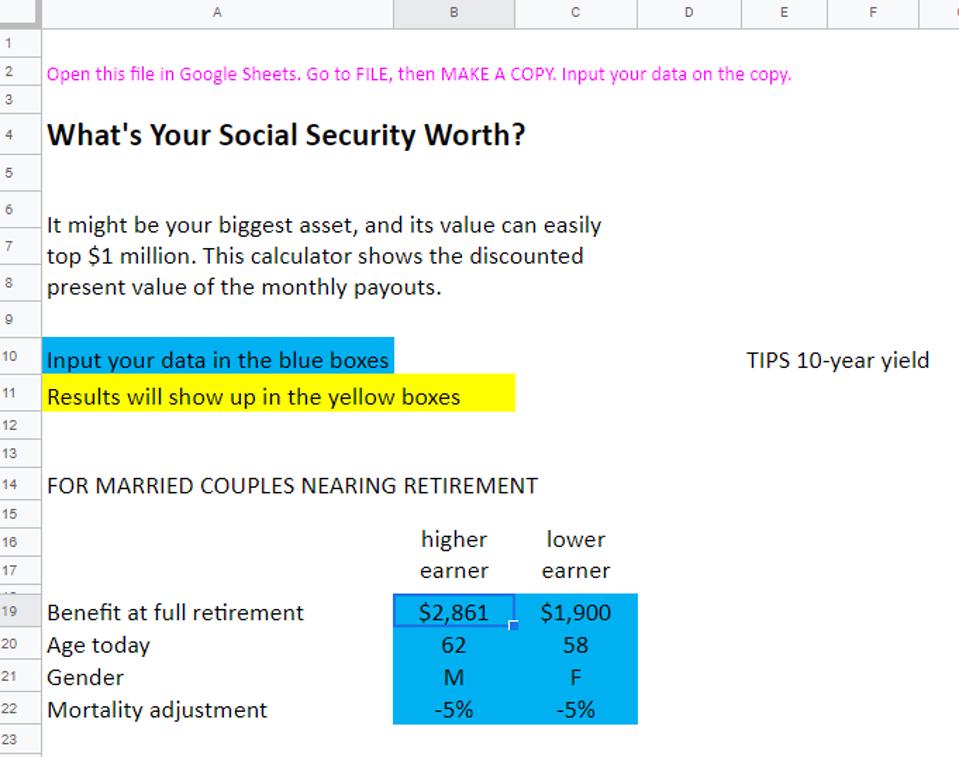

If you are approaching 62 and contemplating when to claim Social Security, go to this calculator. To use it, open the file in Google Sheets, make a copy and adjust ages, health status and other factors on the copy. (Do not “request access” to edit the original.)

Social Security calculator

The discount rates for Social Security payments are the rates paid on TIPS: government-guaranteed and inflation-protected. Those rates are tiny, meaning that a dollar to be paid a decade hence is worth close to a dollar now.

What you’ll probably find is that the payment stream that starts at 70 is way more valuable than the one starting at 62. Early claiming usually makes sense only for retirees who are both (a) sickly and (b) not married to someone with a modest earnings history.

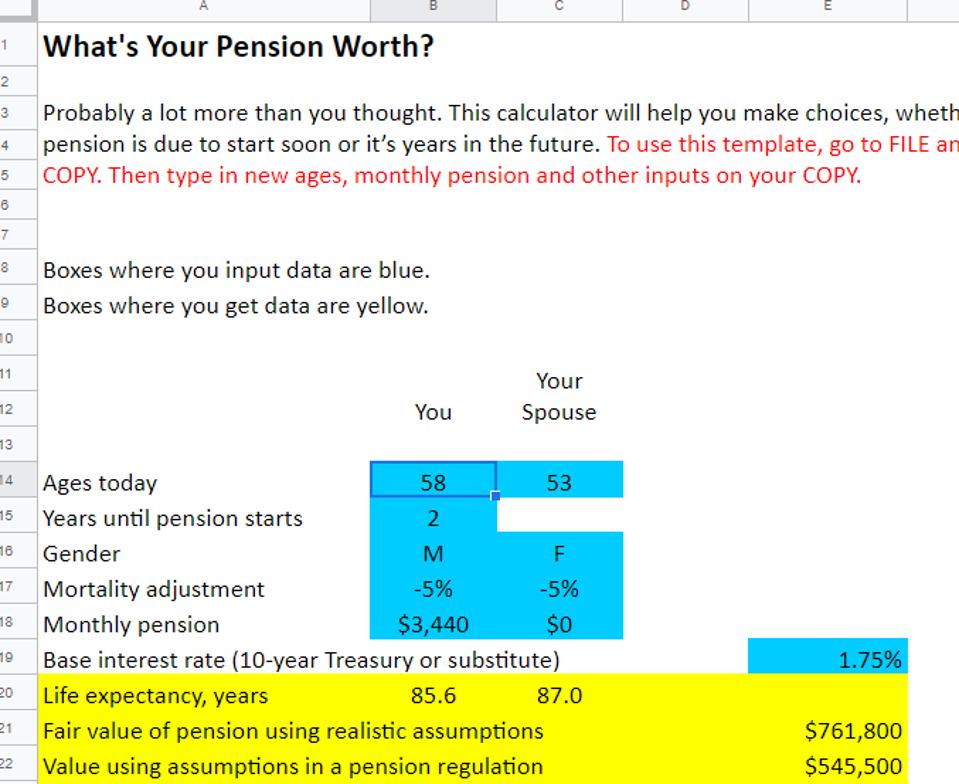

If you are contemplating a buy-out offer on a corporate pension, use this other calculator. Discount rates on corporate payouts need to be higher than on Social Security benefits, primarily because corporate pensions have no inflation adjustment.

Pension calculator

What about credit risk? It’s usually not a big factor. For you to be stiffed on a corporate pension small enough to be covered by the federal Pension Benefit Guarantee Corporation, three entities have to go bust: your employer, its pension fund and the PBGC.

The GE buyout offers are particularly disappointing for the many ex-employees entitled to start collecting at 60. That’s because the offers don’t reflect that early-retirement benefit. You should include the benefit in your calculation.

The PBGC does not backstop payments due from ages 60 to 64, which means that young people do have to kick up the discount rate. But someone now 58 doesn’t have to worry much; it’s quite unlikely that GE will go under before 2026.

Monthly payouts due in faraway years are iffier, but bear in mind that they don’t have much impact on the present value of a pension because you probably won’t be there to collect them.

You’d think that financial professionals would understand that cashing out an annuity is equivalent to selling a bond, and that a bond’s value is not affected by how the seller plans to invest the proceeds.

But I often see experts getting distracted by the seller’s intentions. Here’s what Michael Kitces has to say on the matter of early claiming for Social Security: “The discount rate for financial planning strategies should be the long-term rate of return being assumed in the financial plan itself.” I think that’s quite wrong.